There is no word in English which is as capricious as “mutation”. Shrouded in the mystery of an unknown outcome, these seemingly random occurrences roll the dice in the board game of evolution. Some mutations have resulted in off- centre and quixotic manifestations such as heterochromia and red hair; on the other hand, some of them have contributed to massive advantages such as resistance against malaria and high altitude capabilities. Around Memorial Day 2016, this buzzword of the latest X- Men release would jostled for mindspace alongside the IPL final in India. The study of mutations offers a glimpse into the evolutionary landscape of humans. Often, they yield great insight into the strange means of our world.

Got milk? : As it turns out, the value of milk outside of an ad campaign is enormous as well. Image source: 1.

One of the key moments in the history of the human civilization as we know it today is the development of agriculture. For most of human history, we sustained ourselves by hunting and gathering. The hunter- gatherer diet provided humans with more nourishment and variety; along with it making us nomads, it also added uncertainity to the mix. The antithesis of this was the stability of agriculture, which was crucial for human settlement. Humans began to rely upon a small subset of food crops as they were more efficient and hence supported more population. In relatively short time, the density of human population grew manifold and with it, grew cities. With cities and kingdoms grew the possibility of germination and transmission of new ideas due to the synergistic presence of a critical mass. The far reaching consequences of agriculture on human civilization can be seen even today. However, this was not without its drawbacks- a sedentary lifestyle, lack of diversity, living in close quarters and incomplete nutrition meant that disease and famine often reared their ugly head. Jared Diamond even labelled agriculture as the worst mistake in the human race and termed it the big bang of the class structure, sexual inequality and overpopulation.

Say cheese: Major milestones in the short history of human civilization has agriculture and dairy farming at its helm. Image source: 2

Around the same time as the development of agriculture, adult humans learnt to digest lactose, a key component in milk. Previously, humans would lose the ability to process lactose around the age of five; what was once a main source of food would now cause stomach cramps and potentially life threatening diarrohea. The accompanying digestive discomfort was thought to promote weaning in kids. The mutation proved to have a massive evolutionary advantage- the population with lactose tolerating gene multiplied rapidly at the expense of the others, probably utilizing milk for sustenance when famine struck. Domestication of milch animals also proved to be a handy occupation around the time as the milk could sustain humans in the case of famine. The gene for lactose tolerance thus featured in the perfect storm of agriculture, domestication of animals and human agglomeration (and eventually human settlement). The world would never be the same again.

***

Between 2005 and 2008, the golden goose of cricket, the one- day international, was going through an identity crisis. The Australians had sleepwalked their way to their third consecutive world title; such was the extent of their dominance that their closest victories were by 53 runs (that too by the D/L method) and 7 wickets respectively. The only trophy hitherto unblemished by Australian fingerprints had made it to their cabinet by 2006. They had gobbled up two world titles in 1999 and 2003 as well. They had blown away their closest challengers, India, in the 2003 final after brutalizing them in the group stage; India had made it to the final, crawling through the morass of the group phase, building momentum after the severely debilitating loss against the Aussies. They even required divine intervention from Sachin ”God” Tendulkar to calm down the effigy burning fans back home. The Indian bowling, which had bared canines since the New Zealand tour under the leadership of Srinath (wrapped in cotton-wool), was duly defanged in the final. The 1999 tournament had the Aussies with their backs to the wall with 2 defeats; in 2003, they were briefly challenged by England and New Zealand where they had to resort to their repertoire of tricks. By 2007, their shape shifting, poly- mimetic alloy of a team was at the end of their evolution- they had swatted around the other teams like the countless “bullet fodder succumbing to their wounds in exaggerated fashion” extras in an action movie.

Yellow fever: The insufferable Australians with their third successive ODI world cup trophy in 2007. Image source: 3.

The dominance of the Australians and the farcical 2007 ODI World cup final only heightened the tedium that was the ODI game. Of course, it would throw the odd pleasant result (Bangladesh beating Australia in Cardiff comes to mind) once in a while but the viewers could not shake off the unmistakable feeling of statis. Nothing typified this more than the middle overs of an ODI game; with the fielding restrictions out of the way, the game would meander around a predictable course until the last ten overs. The administrators noticed this too, and in order to enliven the ennui introduced the Powerplay in 2005. The concept of fielding restrictions were anything but new-visions had been sighted in the technicolour World cup of 1992. The fine print would change again in 2008 and would undergo a series of amendments in the years to come.

It was in this environment in which the flight of the Twenty20 format took place- sprouting new wings and soaring high in the sky. The original form of cricket, Test cricket, was an anachronism in the new millennium. One of the most baffling aspects of test cricket to the curious onlooker is its overtly lax attitude towards the fourth dimension- time; the other three dimensions have always been respected in the physics of the sport and its resplendent literature. Playing for five days with no guarantee of a result is another one. Following a test match in the ground amounted to a lot of time, something to the tune of following a player on a miraculous, lung- busting, successive five setter fueled run in the deep end of a grand- slam. Until the supremely time dilated Isner- Mahut match (undoubtedly played on a planet with Interstellar gravity) upstaged all records, the longest ever tennis match was a mere 6.5 hours– the equivalent of a day’s play in test cricket (with an early start to compensate for loss of play) and slightly shorter than an ODI game. It was no surprise then that the game of cricket was first patronized by the aristocrats and the gentry who could use their leisure time for sporting pursuits. In fact, nothing exemplified the symbolism of the prevailing English cultural mythos (the class structure, civil service and the public school system) as well as the game of cricket. The spread of an exclusive game was built on the desire of the conquered royalty aspiring to emulate their imperial masters; this culture of exclusivity is the reason why the game is still played by a handful nations at the highest level today. Without the glue of royal patronage, it is doubtful whether the game would have cast its net far and wide.

I have a dream: (L) Stuart Robertson’s brainchild, the Twenty20 cup, resulted in an upswing in domestic audiences by the time Surrey won the first championship (R). Image sources: 4 and 5.

Attendances for the international form of test cricket were healthy around the year 2000 but the country cousin, first class cricket, suffered due to what can be euphemistically termed as step-motherly treatment from the crowds. The last bastion of healthy turnouts, England, had started seeing the first signs of comatose sporting arenas with domestic attendances dropping by 17% in the five years leading up to 2001. What was especially alarming was that the younger generation was not adopting the game and was passing up the chance to watch other sports- ostensibly, football. The marketing manager of the ECB, Stuart Robertson, who was armed to the teeth with some pretty expensive market research, pointed to a format with a compressed timeslot to suit the ADHD generation. It wasn’t the first time someone had suggested a shorter format- Martin Crowe’s Cricket Max was a forerunner to T20. However, it had fizzled out before reaching English shores. A year later though, it was for real. Despite facing some opposition from the county chairmen, on the back of some last over slogging, the format found a midwife.

All fun at that 70’s show: Hamish Marshall’s afro (L) and the faux red card (R) headlined the first international T20 in 2005. Image sources: 6 and 7.

The scenes of the first T20 international were smeared with mirth; Billy Bowden’s mock red card to Glenn McGrath for impersonating the infamous underarm incident was duly lapped up by the capacity crowd. It was a one- sided cricketing contest played without a whiff of seriousness. Slowly, over the next 2 years, all the test playing nations had played their inaugural T20 game, drawing a mix of curiosity and bewilderment from their supporter base. India were the last test playing nation to embrace the format on their 2006-07 South Africa tour. More famously, India was notoriously lukewarm to the concept of T20; domestically, many other countries had adopted the game early enough. India’s version, organized in mofussil areas, was a damp squib. Why, India’s participation in the hastily organized inaugural T20 World Cup was only ensured after some last minute subtle arm- twisting by Ehsan Mani. India’s grudgingly selected squad reeked of their distaste for the new-fangled format; the team was shorn off their batting superstars. Most of the teams approached the tournament with typical naivety- the tempo, intuition and the wisdom would only come later.

The big bang moment: The success of the IPL was ensured with this scoop shot. Image source: 8.

The short tournament encapsulated every aspect of what T20 was all about; most importantly, it was everything that the 2007 ODI World cup was not. The scintillating tournament showcased the full range of surprises that T20 had to offer- pyrotechnics from the very first match, Bangladesh upstaging the West Indies, a thrilling bowl-out between India and Pakistan, Yuvraj’s Garry Sobers moment which put the match out of range of the Indian bowling largesse and an intriguing matchup between India and South Africa full of twists and possibilities. What the heck, the insufferable Australians were struggling in the format- they had succumbed to Pakistan; their loss to Zimbabwe was the equivalent to the legend of the probably apocryphal Eddo Brandes- McGrath story, adding to everyone’s glee. Cricket minus the jaundiced/ yellow fever/ any other yellow themed affliction was just the shot in the arm the game needed. When the imperious multiple champions lined up against the Indians who had played with a joie de vivre all through the tournament, sparks flew. The mighty Australians were slain by the Indian upstarts with few recognizable stars. Yuvraj Singh played an unforgettable knock that would not have been out of place in another format (Control% of 90) and Sreesanth (remember him?) even managed to needle the Aussies. Joginder Sharma had invoked the spirit of Amarnath in the semis and final (not quite in the same league but the comparision featured heavily- no doubt weighted by the euphoria of the victory- in the discussions amongst portly, balding old men with enlarged prostate glands) with a firm nod to the 1983 victory.

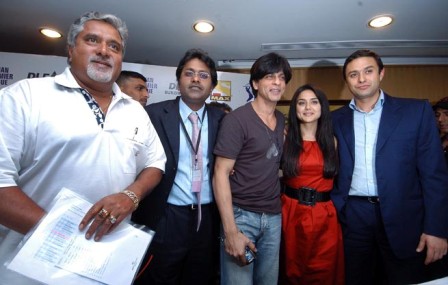

Star India parivar: The fraternity of the rich and the famous came together to create the biggest show in town, the IPL, in 2008. Image source: 9.

By the time the Indians had won the tense, cagey final of the World T20, to paraphrase and misquote Victor Hugo, no BCCI could stop the idea of T20 whose time had come. India lapped up the new superstars and after prize money was doled out by the millions, they were household names, though, not quite ingrained enough for the public to name their kids after them. When IPL was launched in low- key fashion just days before the Indian victory, no one could have envisaged the eventual impact it had on the world of cricket. With BCCI emerging as the victors against the ICL in the fistfight for hosting a T20 league in India, it had unrivalled access to a virgin market smitten by the format. The plans for a league had been years in the making as an ODI league, envisioned by the all- powerful Lalit Modi. Meanwhile, the Indian team walloped the Aussies at home, much to their dismay, in front of a full house at Mumbai. The Aussies didn’t forget this defeat – they would hand in one of their own in Melbourne a few months later. The feeling of levity was still hard to shake-off from the latter T20 contest in early 2008. I particularly remember Gavaskar thundering at seeing the name “Catfish” printed on James Hopes’ back. I only wonder how he would have scowled at fans getting their hands on the India cap due to the latest merchandising deals brokered by the BCCI. When the IPL auction with their superstar owners rolled into town, the stock market sentiment leading to seven figure salaries worked up quite a bit of bile amongst the cricketing establishment and the public. The first murmurs of the ODI format’s death started to appear around the same time; one suspects that if not for the biggest, most prestigious open prize in cricket, the ODI World cup (The Ashes are off limits to other countries), present commercial interests and the unpleasant prospect of expunging ODI records from the game, the utility of the ODI format would have been reevaluated in the face of T20’s popularity.

After the novelty of the T20 format died down and the vacant summer was filled by yet another T20 match every day, the first cracks began to show. Come every prickly summer, along with the appearance of seasonal fruit, prickly remarks against the IPL find favour and flavour in print and online media. The act of missing the IPL is bestowed a badge of honour by the intelligentsia, usually annoyed by the hoi polloi enjoying themselves at the grounds, watching the game. Upsetting the established system (disruption is buzzword in vogue now) and patrons was bound to be unpopular. For the ones accustomed to the mellifluous tones of Benaud and Arlott, the IPL was one big advertisement. The IPL has been justifiably derided for being garish and loud, a contemptuous remark which was typically reserved for the nouveau riche. The subtext is not lost in an English game symbolized around the notions of the class structure. The hallmarks of test cricket – traditional, genteel, rooted in understated elegance of the aristocracy were uprooted by the noisy party down the street organized by the new money. Very soon, it became a lightning rod for criticism, attracting opinions from everyone (including me) who had an axe to grind. Losing in test matches? Blame the IPL. Can’t find bowlers? Blame the IPL. Global warming Erosion of moral values in society? Blame the IPL. How did the IPL respond? The only way it knew- by throwing more money at it and turning the volume of the music up a few notches.

Even though the format is a magnet for criticism, a lot of it is déjà vu all over again. It is worth remembering why the ODI format was born in the first place; literature chronicling the origin of the first shorter format game is particularly revealing- it was invented in order to bring more people to watch the game and to avoid financial losses. The premise and the low key births of the ODI and the T20 format are eerily similar; so are the ways they were devoured by the audience, jaded by the banality of the longer formats. Both these formats were not new in their origin; vetting by the powers and widespread acceptance took time. The first world cup for both formats, envisaged on a tightrope walk, was shrouded by the sense of not knowing what to expect. History repeated itself when people were sceptical of a spinner doing well, commented on the frivolity of the format and compared it to selling one’s soul. India were similarly very slow to take on the gimmicky format and it was only after they won their first World cup did their eyes open towards the possibilities of the game, commercial or otherwise. How a professional cricketer could earn his living was answered with launch of the league- based Packer backed WSC and the shoehorned IPL. We don’t know the full impact of the latter just yet. Thus, many of the events and criticisms of the shorter formats repeated themselves, albeit with a new generation of fans.

Controversially yours: The many headlines of the IPL caught with its pants down. Image source: 10.

This is not to say that the T20 format or the IPL is free from faults. Like the mightiest dams, many of the protestations hold plenty of water. It has sold every square inch of space and every possible second of ad time to make for an unpleasant, ultra- consumerist exercise. The IPL represents the worst of the Indian way of life with corruption, conflict of interest and crony capitalism rearing its ugly head. Just as the appearance of a sugary confection is bound to attract ants, people of all hues, shapes, forms and intentions throng to associate themselves with cricket for a wide variety of reasons- it all comes with the territory. It is not unreasonable to expect a person who has invested heavy sums of money to run it like a business- with profit being the central tenet. The T20 format lends itself to the commercialization of cricket- every interruption by the bowler to tie an undone shoelace over has an ad- break.

| Format | Innings | Wickets* | W/I* | Balls | B/W* |

| Test | 7985 | 67643 | 8.47 | 4581745 | 67.73 |

| ODI | 7400 | 53051 | 7.23 | 1982651 | 37.05 |

| T20I | 1100 | 7038 | 6.39 | 128187 | 17.50 |

Table 1: Wickets per innings and strike rate statistics for tests, ODIs and T20Is respectively. * Wicket for a bowling team includes run outs.

The other form of criticism is based on the format of the T20 game itself. It has been argued correctly that T20 is not a format of the game of cricket as we know it; the essential argument used against the format is that the carrying over the rules of the ODI game warps the sense of balance between the bat and the ball. The teams that stack up modest bowlers who can deliver the big hits (rather than a frontline bowler) and that muster more big hits often win more matches. The recent World T20 2016 finalists also seem to back up this assertion. The backbone of the argument involves conjuring of the rabbit out the hat- Chris Martin. One of the most vociferous detractors of the T20 game is Kartikeya Date, who peddles the argument that a team of 11 Chris Martins (with a test batting strike rate of 11.8 balls per dismissal) would almost survive the bounds of a normal T20 game. While this line of attack does exaggerate how loaded the format is in favour of the batsman, the very example chosen to highlight the issue itself is not fair dinkum.

On an average, the wickets claimed by the bowling side (inclusive of runouts and extras) is ~8.5, ~7.2 and ~6.4 per inning of Test match (W/I), ODI and T20I cricket respectively. The corresponding balls/ wicket (inclusive of runouts and extras) for a bowling team (B/W) is ~68, ~37 and ~17.5 for the 3 formats. Meaning, a bowling side typically takes ~11, ~6 and ~3 overs respectively to obtain a wicket in these formats. However, the circumstances and premise of wicket taking take different meanings in different formats. The bowler usually plays the match winning hand in test cricket and a batsman’s role is limited to avoiding defeat by means of survival; a win is usually as probable as a draw when the batsman scores well. In other words, unless a side manages to take 20 wickets (or otherwise aided by declarations), it will not win a test match. On the other hand, piling on the runs is no guarantee of victory. Since the number of balls in a test match day itself is very high, the gargantuan achievement of a daddy hundred often results in batting the number of balls equivalent to an ODI match. As a result, apart from the exceptions of a tense/ high run- rate chase or a quick declaration, the batsman is under no pressure to score a run off any given ball in a test match. Hence, accepted wisdom dictates that a good test batsman must eschew risk and punish only the bad balls in order to maximize chances of survival.

All fast but some furious: Not all fast bowlers were treated the same by the T20 format. Image source: 11.

The cricketing axiom of taking wickets to win the game vanished with the ODI; victory by run containment changed the dynamics of the game completely. The very same ODI, which was invented as the antithesis of the statis in test cricket- which lacked the resolution of a result in dull draws. Teams could not hope to bat for time in this format as the constraint of runs would prevail while determining the end result, so crucial to this format. More importantly, teams could now afford to bat well and just contain runs rather than take wickets. A bowler is essential for victory in test cricket; a bowler who could test and probe a batsman, ask questions and coax the batsman to make a mistake when he is not under an obligation to score runs is highly regarded. Whereas, a bowler is slightly more than an accessory in the ODI with this run containment angle. This is primarily the reason why pure all-rounders (by the classical definition of being independently eligible either as a bowler or a batsman) are the equivalent of a blue moon in test cricket. Not only are they expected to take wickets like a frontline bowler but they are also expected to shoulder responsibility when summoned to bat (as ~8.5 wickets fall per innings in test cricket). They are more far more commonplace in ODIs as they’re required to bowl a few tight overs (and not necessarily take wickets) and only bat out a limited set of overs as 6 dismissed batsmen in ODIs gobble up 222 out of 300 balls on an average (at 37 balls per dismissal). The devaluation of the bowler started in the ODI due to limiting the contest; it is only natural that the T20 greatly exacerbates the original balance of cricket. The value of a hattrick has fallen too- three wickets in three balls in test cricket is a work of art in test cricket considering that three batsmen avoiding risk have been snared by the bowler; the corresponding achievement in T20 cricket is highly devalued considering that the batsmen pay little heed to their survival. Thus, the pure test match bowler who can deliver a wicket by beating a batsman who has very little obligation to score or take risk is indeed an endangered species in the T20 format.

| Format | Innings | Wickets* | W/I* | Balls | B/W* |

|

Since T20 |

|||||

| Test | 1720 | 14625 | 8.50 | 922284 | 63.06 |

| ODI | 2986 | 21808 | 7.30 | 786009 | 36.04 |

| T20I | 1100 | 7038 | 6.39 | 128187 | 17.50 |

|

Since T20, First innings only |

|||||

| Test | 466 | 4359 | 9.35 | 290975 | 66.75 |

| ODI | 1510 | 11872 | 7.86 | 425059 | 35.80 |

| T20I | 552 | 3692 | 6.69 | 64619 | 17.50 |

Table 2: Wickets per innings and strike rate statistics for tests, ODIs and T20Is respectively since the advent of T20Is . * Wicket for a bowling team includes run outs.

Now, back to the numbers- the metrics of bowling team wickets/ innings and balls/ wicket do not change greatly for test matches and ODIs since the time of T20Is. The W/I increases by <1% and the B/W reduces by <7% since the first T20I. If one has to observe how a team would react in an unfettered way in the absence of a target, only the first innings statistics have to be considered. Since the first T20I, the first innings bowling side has pouched >5% extra wickets per inning and has shown contrasting stats for B/W (>10% increase in tests, <1% in ODIs and identical stats for T20Is) in the 3 formats. Since the introduction of the T20I, test teams have batted longer and ODI teams have taken more risks. In T20Is, the number of wickets per innings is ~6.4 since inception. These numbers increase to ~6.7 wickets per innings when the constraint of having to chase a score is removed (first innings only). Correspondingly, the balls per wicket (To reiterate, this is based on team bowling stats which includes extras and run- outs) ~17.5 balls or once every 3 overs. Since only ~6.4 wickets fall on an average, the lower order is rarely tested and hence wickets are devalued. Since the T20 game is all about purely about scoring runs (by whatever means), a premium is placed on batsman who plays big shots; run containing bowlers who can deliver the big hit are selected over bowlers who can deliver wickets. If the central battle of test cricket was wicket taking versus survival, the T20’s central battle is run scoring versus run containment. The only other metric that defines the devil may care attitude of T20 batsmen as well as the 3 overs/ dismissal is the Control% (no. of balls the batsman was in control of the shot). Mining and analyzing Control% data from previous years has shown that teams in control win the T20 match more often than not; and also that batsman in T20Is gamble for a much lower ~75% Control% in their pursuit of quick runs.

In fact, no other quote sums up the nuances of the different formats of cricket better than this one by Freddie Wilde, in the very same article where Date and he debated about the T20 format at length:

“First-class cricket is defined by the struggle for survival and the struggle for wickets. One-day cricket is defined by the struggle for runs within the struggle for survival, and the struggle for containment within the struggle for wickets. T20 cricket is defined by the struggle for runs and the struggle for containment. And these gulfs in definition are being widened as T20 continues to radicalise and pull one-day cricket with it.”

The T20 format and its ad-men were clever enough to base their branding strategy around batting rather than bowling; bowling would yield only 10 instances of a joyous occasion but basing it on boundaries would yield a lot more in comparision. One more thing that is widely lamented in the T20 format is limiting a bowler to only 4 overs per match. Considering that test match bowlers and batsmen can, in principle, rack up 50% and 100% of the balls bowled to their account, the ODI seemed as a major compromise, especially for the bowler. A batsman could bat for a full 50 overs but a bowler could only bowl 20% of the total quota. In test matches, the lofty Bradman and Murali are well ahead of the pack and accounted for ~25% and ~39% of their team’s runs and wickets respectively. However, research by Anantha has shown that even the best ODI batsmen scored less than 20% of their team runs, which would imply that the ODI format got this balance through some sense of intuition during its inception; I’m pretty sure this does not hold true in the T20 format as top order batsmen dominate and are more likely to have a bigger share of team runs (well over 20%) as opposed to the bowlers (who are limited to 20% of the overs bowled).

Degrees of separation: A B de Villiers playing very imaginative shots around the ground in the shortest format. Image source: 12.

T20 requires a different premise, skills, thought process and mentality when compared to test cricket. A good length ball on the fourth/ fifth stump may be a great ball in test cricket and a bowler can probably bowl six of those in succession to a skilled batsman who will let it pass harmlessly (after accurately judging its trajectory). Whereas, a similar approach in T20s will probably be disastrous for the bowler and the ball will mostly be dispatched to the boundary using a totally different set of skills. Likewise, a slower ball is more likely to produce a wicket in T20s, where change of pace is akin to the permutations of the placements chosen by a team running in to take a penalty shootout. In a test match, slower deliveries are used very rarely due to the low wicket taking return. Simply put, T20 is a different game which only resembles the traditional form of cricket in its rules and some gameplay. Considering their differences, the vitriol is both unnecessary and uncalled for. To compare it to test cricket is a great disservice to both; it is more like comparing a good, nuanced, long form article with a pithy tweet. Turning the earlier argument around (in a similarly unfair vein), if a test- mode Dravid (I hate myself for using one of my heroes to make my unfair remark but it needs to be done to show what a stretch the previous remark was) were to bat in T20Is with his 123 balls/ dismissal and 42.5 SR, he would carry his bat through the innings and score 51 risk free runs without getting dismissed even once. More importantly, he would lose the match (and probably every other match as well).

Looking at some of the previous points, are T20Is and leagues like the IPL bad for the game of cricket? Far from it. What could be argued in favour of the T20 format? For starters, the money part of it. Organized sport (and this is especially true of the game of cricket) in its infancy (in the 19th century) placed a high emphasis on playing a game for the love of it (rather than playing it for financial motives). Not surprisingly, this was the prevailing view of the aristocracy who had found new ways to utilize their leisure time after striking it rich with the industrial revolution sweepstakes. Playing organized sport was the sole preserve of the amateur sportsman (one who played out of love for the game) and it took generations to erase the stigma of being a professional (one who played a sport for financial benefit). Cricket, being aristocratic in its origins, symbolism and literature, the game that did not see an English captain from the professionals until the 1950s, has always been uneasy with the role of money.

Fans of the same franchise flock together: The IPL has been able to bring crowds that were hitherto the preserve of the home international matches. Image source: 13.

For a long time, the England County / league circuit was the only place where professional cricketers could earn their living. Until Kerry Packer pulled off his coup, even Australian cricketers were essentially paid an amateur’s wages. For all the BCCI’s riches, it only increased the match fees when the ICL threatened to pull the rug under its feet a la Kerry Packer; the central contracts sweetener in addition to match fees are only a recent phenomenon. Considering that most sportspersons live an extremely short life with peak earning capacity (as opposed to people with regular careers in other professions), it was laughable that only a handful of India’s cricketers could earn their millions while the rest of them waited in the wings in domestic obscurity. To make matters worse, apart from the few lucky men who made it to the Indian team, the opportunity cost of a normal career was significant until the IPL came along. Today, a couple of hundred cricketers and their support structure earn their living and not many would have looked back at the opportunity cost today. In fact, players from the majority of Test playing nations stand to earn a more comfortable living playing league based T20 cricket and have a strong financial reason to choose club over country. What the IPL has done successfully is to generate an ecosystem of financial security for players, coaches, scorers, umpires, groundsmen, commentators, kit men, food contractors and spectator paraphernalia sellers (some would add bookies to this list) and interest about the game from new territory. In today’s times, we have to admit that the T20 is the only cricketing format which fits in with the working man’s (or woman’s) timetable. It is also undeniable that the T20 format is the only format that shines the spotlight on the players by putting consistently bums on seats even in domestic cricket. This has been replicated in the BBL and the Women’s BBL as well.

What about spin bowling? Spin bowling was supposed to disappear in the age of T20. According to popular wisdom, spinners, with their slow, loopy actions were supposed to be cannon fodder. Thankfully, the truth flew in the face of popular cricketing logic. The T20 format has given a serious shot in the arm for spin bowling. Teams are yet to embrace using the spinner in the death overs but they feature heavily in every team’s bowling plans and often put the brakes on the opposition score. Besides, Test cricket wasn’t exactly free from the blame of dishing out some step-motherly treatment of its own; in the abyss that was the 1980s, spin, especially wrist spin, was isolated and quarantined like a contagious disease. Teams and captains, in a nod to the prevailing free- market Reaganomics, began to question the value of return on investment on spinners, especially leg- spinners. Spinners were often relegated to defensive roles and little encouragement from test captains, so much so that the top spin bowler from the fallow decade averaged over 32 runs per wicket.

Passing the baton: Ever since their first sighting, relay catches have made regular appearances in the T20 and have percolated into the longer formats as well. Image source: 14.

The T20 has fulfilled a vision from the blur that was the Inzamam run out by Rhodes in 1992 and has effectively put it on steroids. Due to the infinitesimal victory margins involved, the art of fielding in T20s lends itself to scavenging the ground in order to save every last run. Relayed catches, which were once the stuff of dreams a generation ago, are common sightings today. No target is safe today- with the batsman ever alert to the possibility of a run, having been taken to the limit of his evolution in the T20 format and its concomitant effects on test cricket. In the recent Ashes series, only two batsmen who had played 240 balls had a control% in excess of 85%. On the other hand, the statistics from the previous editions of the IPL show that the batsmen were in control ~75% of the time (note that these stats are from 3 recent editions of the tournament), a statistic which plateaued after a batsman had played ~4 overs. It is remarkable that the T20 batsman is able to score close to three times the runs scored in a test match over by just losing control for a additional ball for every 10 faced, even in the case of the longer innings. Granted that the premise, field settings, mentalities and pitch conditions are oceans apart in the two formats, but it speaks volumes about the adaptability of today’s batsmen towards playing percentage cricket. In fact, the recent World T20 has shown that the dynamics of the format w.r.t scoring runs and being in control is not a zero sum game, especially in the cases of Virat Kohli and Joe Root.

Spreading the joy: No other format has made the game more welcoming to the newcomer as compared to the T20. Image source: 15.

Perhaps the greatest impact of the T20 format is how it has moved away from the shackles of the insular, inward looking world of cricket and made a newer set of people part of the process. Since the games are shorter, it is easier for the older player to partake in the format as an equal. The format has given a foothold for the new teams too; for a very long time, the reigning cricketing powers of cricket have reined in cricket’s spread by adopting a rather patronizing attitude towards the new teams. In the days of cricketing yore, countries faced the condescending ignominy of a patronizing MCC side and sometimes, even faced off against a second string English team. This behaviour of exclusivity has recently manifested itself in many ways, effectively stymieing the entry of a new country into elite level sport- may it be granting test status or by proposing to cull the number of associates for the next world cup. Stories from the “associate” world are filled with heartwarming tales of passion, love for the game and tremendous uncertainity and the slim pickings provided by the ICC are not commensurate with what the associates put into the game. The world cup is the last hope that an associate nation has in getting to play a good cricketing nation and improve themselves. How do teams get better- by only playing more- how do they get to play more- by only getting better is the catch-22 of the cricketing world. By cutting out the mandatory exposure that a fledgling team needs against a good team, their game is deprived of oxygen in their infancy. By culling the willing participants in order to make the game more “competitive”, the administrators are only preventing the spread of the game in the long run.

| Name of team | No. of matches for first victory | No. of matches for first victory against Eng or Aus |

| England | 2 | 2 |

| Australia | 1 | 1 |

| South Africa | 12 | 12 |

| West Indies | 6 | 6 |

| New Zealand | 45 | 113 |

| India | 25 | 25 |

| Pakistan | 2 | 9 |

| Sri Lanka | 14 | 45 |

| Zimbabwe | 11 | – |

| Bangladesh | 35 | – |

Table 3: Time (in terms of matches) taken for a team to win its first test.

Once upon a time in Chennai: Heroes of India’s first ever test win, Vinoo Mankad (L) and Vijay Hazare (R). Image source: 16.

Before the emergence of the T20, the game of cricket was ridiculously difficult for the outsider, more so, test cricket. The world’s newest test playing nation, Bangladesh, was inducted into the cozy, exclusive club in 2000-01 season. Ever since that day in November 2000, it has played 93 matches to date and has won only 6, that too against Zimbabwe and an impoverished West Indian team. Needless to say, it has the worst ever record in test cricket. It has fared a lot better in the ODI format, finally turning a corner with impressive home series wins against Pakistan, India and South Africa. The ODI format may have some memorable upsets to its account but the world of test cricket is not so similarly rich. Expanding this theme further by examining test cricket’s newest inductees at their time of initiation tells a tale of their struggle for existence, relevance and respect. Teams took a very long time to win against the established teams, England and Australia (We’re not talking about away victories here). South Africa and West Indies beat depleted English teams when they won their first match; India eventually managed to beat England at home in their 25th match; New Zealand and Sri Lanka took years to register their first win and almost forever to win against one of the two oldest sides. Pakistan was the lone bright spot, winning in only their second test match and beating England in their ninth. However, it must be remembered that they retained a critical nucleus of players from the Indian team post- partition. The two newest members are yet to win a game against England or Australia.

| Name of team | No. of matches for first victory | No. of matches for first victory against a test team |

| England | 2 | 2 |

| Australia | 1 | 1 |

| South Africa | 3 | 4 |

| West Indies | 2 | 2 |

| New Zealand | 1 | 21 |

| India | 4 | 14 |

| Pakistan | 2 | 2 |

| Sri Lanka | 6 | 8 |

| Zimbabwe | 1 | 1 |

| Bangladesh | 23 | 35 |

| Afghanistan | 1 | 30 |

| Canada | 4 | 4 |

| Ireland | 2 | 10 |

| Kenya | 5 | 5 |

| Netherlands | 13 | 58 |

Table 4: Time (in terms of matches) taken for a team to win its first ODI.

On the other hand, teams that have played the ODI World Cup have taken far fewer matches to notch up their first victory against a test- playing nation (some of these numbers are inflated considering that the bigger teams did not play the “minnows” outside of the world cups) in the ODI format. Stretch this further to the canvas of a T20I, every team that has played in the World T20 has tasted victory by the time they played their fifth match; barring Afghanistan and Scotland, all other teams have beaten a test team within their first five matches as well. Considering the reasons specified previously, the inflation- adjusted figures (considering matches against test playing nations only) for Afghanistan and Scotland are 7 and 4 respectively.

| Name of team | No. of matches for first victory | No. of matches for first victory against a test team |

| England | 1 | 1 |

| Australia | 1 | 1 |

| South Africa | 3 | 3 |

| West Indies | 2 | 2 |

| New Zealand | 2 | 2 |

| India | 1 | 1 |

| Pakistan | 1 | 1 |

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 1 |

| Zimbabwe | 2 | 2 |

| Bangladesh | 1 | 4 |

| Afghanistan | 2 | 32 |

| Hong Kong | 3 | 3 |

| Ireland | 1 | 5 |

| Netherlands | 1 | 5 |

| Scotland | 4 | 13 |

Table 5: Time (in terms of matches) taken for a team to win its first T20I.

The reasons for the disparities between the results in different formats are fairly obvious. The longer the duration of a cricketing game, more often than not, the better team wins. The gulf in ability inevitably shows up sooner or later. Scaling this down to the T20 shrinks the margins even further, with the correlations between team and individual performances getting muddled up. Random events of chance such as edged boundaries or an uncharacteristic unplayable delivery end up influencing the result more (as compared to skill) in the shorter formats. More number of matches with closer results are observed in T20, the artifact occurring due to the design of the format. In a nutshell, the format is the most forgiving to the underdog, the biggest story there is in any sport; and therein lies T20’s biggest legacy.

Every underdog has its day: One of the most enchanting sporting miracles of all-time, the Leicester City premier league victory. Image source: 17.

Felling a Goliath has always been fashionable, right from Biblical times. The epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata feed on the spirit of the underdog against all odds as well. Before the magnetic appeal of the greatest sporting underdog story of all time, the Leicester City English Premier League title bid (a 38 game league mind you, and not a series of successive single legged, knockout cup- ties) the footballing audience were hooked on to the allure of Jurgen Klopp’s Dortmund and Diego Simeone’s Atletico Madrid going toe- to- toe with the European elite. After the giant oak of Sampras was felled at Wimbledon in 2001, the crowd seemingly shifted loyalties to the mercurial Goran Ivanisevic. Stories like these feature heavily in The Cricket Monthly’s list of greatest test performances in the last 50 years, emphasizing the enthralling nature of these stories.

Perhaps science can explain why people are drawn to the captivating charm of an underdog story. Scientific research has talked about how people are drawn to disadvantaged figures in a contest, explaining about how they perceive their endeavour to compete on even terms as significantly more effort. To paraphrase the findings of this study, spectators are more drawn to the appeal of supporting a team with odds massively against its favour; this even overrides the negative effect of backing the loser. Willing a handicapped contestant to win in the heat of a sporting match of great significance is the raison d’être of even the most battle hardened, cynical viewer of sport. It is also not surprising that many politicians and businesses harness the power of the underdog to subliminally influence their target audience.

Different cricketing nations have paid homage to this underdog spirit, often with a sense of gratitude. This narrative of the path to sporting competence has followed the same template, albeit with different protagonists. The recurrent theme is based on a bunch of talented individuals, forged by adversity, brought together by inspirational leadership- Lloyd’s West Indians, Kapil’s devils, Border’s breakout moment, Imran’s cornered tigers, Ranatunga’s World Champions, Akram Khan’s pathbreakers and Dhoni’s brave new generation. Looking back, it is natural to associate the galvanizing effect of these victories on the psyche and self-esteem of cricketing nations. But the relevance of victory should not be especially forgotten. It was India’s 1983 seismic win that changed the cricketing landscape and brought the world cup to the subcontinent through some canny negotiations. In the recent world cup, nations such as Scotland, Netherlands and the Indian women were chasing victories in the hope of better treatment from their peers and administrators. Triumphing against the odds to discover new realms of possibility is the ethos of sport; a microcosm of life; and the story of survival, the ultimate motive of evolution.

***

The story of cricket today is the one of transformation and evolution. The freakish, mutative results in the events of 1983 and 2007 have had a huge say in the way the sport has been conducted and consumed in today’s times. Cricket, in its pristine form, survived initially due to the patronage of the aristocrats, and later, on the back of new found leisure, as a by-product of an economy enriched by several generations of riches of imperialism and the industrial revolution. The game spread due to the centripetal force of imperialism and monarchy; it is not hard to see the correlation between their eventual dwindling influence and the appearance of the first shorter format. If the game had been launched in the last fifty years, without the glue of the imperial masters, it would have soon become a relic, much like monarchy itself. More importantly, if the game had not evolved itself to the time-frames of today’s audiences, the servants of capitalism, it would have been eventually untenable, slowly regressing to the genteel amateur times of the English countryside, with a sparse audience of friends and family watching each game.

Who kept the crowds out: Test cricket does not have great footfalls in many parts of the world. Image source: 18.

The T20 format (and the ODI, before it) deserves a large portion of the credit for reinvigorating the game, and, more importantly, for paying the bills. The fabled 1991 Ranji trophy final might have drawn a sizeable crowd close to its denouement in its time, but the deathly silences greeting the Ranji trophy is a far cry from the atmosphere a few decades ago. By putting the spectators, the lifeline of any sport, back in stadia (this is also why countries are making a beeline for day- night tests), it is thoroughly deserving of our respect. It is the right format to globalize the game as it competes on even terms with the timeframe of other sports and entertainment avenues. The idea of T20 would reach its next logical post script by making the WorldT20 open to more countries by playing the World cup two years and by introducing it in the Olympics. The WorldT20 would then not be a joke like the self- aggrandizing World Series tournaments in the United States, taking the audience beyond the traditional two hand count.

In the era of 140 characters, a pithy or snarky punchline might rule over any given sentence of a great novel; but when done right, in the context of its narrative, character arcs and layered plots, the nuanced, longer form can sell more copies and create more memories than a retweet. Yes, the T20 format is not perfect and the rules of the game could be reexamined (to reduce the number of wickets to 6 or 7, for example) to address the issue of balance between bat and ball so that it compares favourably with the other formats of the game. Unfortunately, it would happen at the cost of the underdog, thus removing the lower entry barrier for a newer cricketing nation, the very USP of the format. The T20 format has passed the ultimate litmus test of having healthy crowd and TV viewership figures for the non- home team matches in the subcontinent, the death knell of the Champions league T20. The way A B de Villiers has been cheered throughout the recent India- South Africa bilateral series indicates that the IPL has made its mark, moving beyond the confines of parochialism (and the accompanying jingoism) to appreciation of a sportsperson for his/ her skills. That the IPL tournament exists and comes back year after year with a vengeance in spite of costly overheads suggests that the league is in rude financial health (although the same cannot be said about its other counterparts around the globe).

The original pleasure of test cricket originated and grew as a product of the surrounding economic and socio- political milieu of its time; it would be foolish to expect the game not to be a slave of the prevailing conditions today. The tapering off of test match audiences are a by-product of today’s economy- one could successfully wager that only a handful of privileged men (and women) can afford to take many days off to watch their beloved team in the flesh or on TV; following the travails of a domestic team, away from the spotlight of popular fandom, over the course of a season cannot be called anything but a profligate habit for an adult making a living off the daily grind. The reality of today’s economies built with a capitalistic subtext and on the guiding spirit of demand dictates that any leisurely activity has to jostle and co-exist with a working man’s timetable. If cricket has global ambitions, it needs a form of the game which is in sync with audience participation worldwide. It is not surprising that the mother nation, England, has embraced the shorter formats with a renewed enthusiasm recently.

The T20 format is certainly not the green- eyed monster that the bunch of curmudgeons profess it to be; it would not be wrong to state that the format is indeed cricket’s lifeline. There is a necessity to treat T20 with normal vision, away from the hyper salesmanship laced megaphone of the IPL (and its ilk) and the concomitant vitriol from its detractors (me included), not too dissimilar in spirit to what greeted some of the world’s most path- breaking inventions during their early years. Cricket has already made the switch from the times of monarchy and imperialism; by being sponsored by today’s royalty, the big corporations, and bowing to the will of the people, democracy in a loose sense, it has stayed in tune with the times in the ocean that is today’s metropolises; a place where the parochial gives way to the appreciation of the professional; immigration, displacement and frequent job changes are a way of life in search of opportunity and paying the bills; and a time where one is known to have multiple loyalties rather than fit a monochromatic stereotype.

It would be hard to imagine the technological advances of today happening in a hunter- gatherer human society. The human civilization owes much of today’s lifestyle to the advent of agriculture. Similarly, the development of technology in the game of cricket (drop- in pitches, floodlights, third umpire, snickometer, real- time ball tracking and the others) coincided with the arrival of the ODI format. The mutation of the game to form T20 has taken this further, not unlike the gene for lactose tolerance, and ensured the survival and relevance of the game of cricket in a global arena. The shorter formats also guarantee stirring the teams in the competitive mix in order and producing results which are more encouraging to the newcomer; with the purge even bringing a smile to everyone’s face once in a while with an unlikely victory (like the once in a generation Premier league title victory). Make no mistake, cricket has gained more from the adoption of shorter formats than having been adversely affected by it. In a nod to real- life events, if cricket had clung on to the ideals of the ethos of the game of cricket and strived to play it in the longer (timeless) format, it would have missed the proverbial bus (in this case the ship). The alarm bells, from the neonatal beginnings of every cricketer- amateur cricket, ring loudly in the background and in its context, the arrival of T20 could not better timed. The game of cricket need not be vary of the money, brought in by the T20 format, needed to run the game at the global level. Administrators would do well to note the strange equation that cricket and money have had since the days of colonial empires past and follow their lead:

“Cricket in its history has done both, sometimes simultaneously, although generally one or other predominates. When English cricketers first came to Australia 150 years ago, it was primarily to make money; when Australian cricketers began reciprocating those visits, it was chiefly to satisfy a colonial longing to express both rivalry and fealty.”

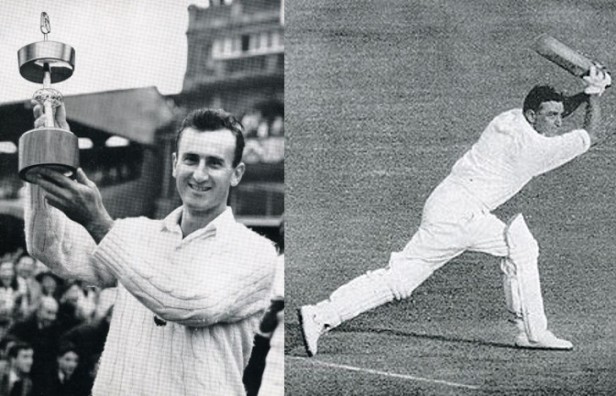

Rising from the ashes: The first Gilette cup, won by Ted Dexter (L), was born out of the ashes of Gentlemen vs Players fixture. Wally Hammond (R), would have certainly approved of the new social order, having to turn amateur in order to become England’s captain. Image sources: 19 and 20.

To answer the seminal, existential question preceding these sentences, “Does cricket make money in order to exist, or does it exist in order to make money?”, cricket needs to make money for it to grow and have a global following. If beloved test cricket has to survive, it will have to do so under the refuge of T20s. Perhaps, the answers lie in moving the highest form of the game to association cricket and franchise based test cricket and making it the most remunerative, like the other sports around the world. It would be the ultimate revenge of the professional cricketer should this happen; deprived of captaincy, standing, respect and opportunity through the game’s early history, their tribe would certainly rejoice and find solace in their status no longer being pejorative. Wally Hammond and Bob Barber would have certainly approved of it, having suffered professionally in the holier-than- thou era of the amateurs. Test cricket? It would be the last few protected luxuries left in the world with its longer survival well ensured by the T20 industry, the one that ennobles the professional, puts bums on seats, is elder friendly, gives the underdog a chance and pays the bills so that the artistic pursuits and can be pursued by a privileged few at a very high level of prowess. To quote John Adams,

“… I must study politics and war, that our sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. Our sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history and naval architecture, navigation, commerce and agriculture in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry and porcelain.”

Disclaimer: Some images used are not property of this blog. The copyright, if any, rests with the respective owners.