On Sunday, the much-hyped contest between traditional rivals India and Pakistan turned out to be—literally and figuratively—a damp squib. All the buildup to the match focussed on how the teams had to handle the pressure and perform; ultimately, only one team—India—turned up on the field. They played with a confidence and assuredness that fans of another vintage could only dream of, and in clinical fashion, dismantled the Pakistani team. In short, it was business as usual.

For fans who have watched this team in action over the last three calendar years, the result wasn’t entirely unexpected. Since January 2017, India’s record reads: 65 matches played, 46 matches won; a Win-Loss (W/L) ratio of 2.875 (nearly winning 71% of the matches). In this time period, India made the 2017 Champions Trophy final (where they lost to Pakistan), and won all other series apart from the away one in England (where they ran the hosts close), and the recent, unexpected reverse at home to Australia. All this begs the question—is this India’s best-ever ODI team?

There are many ways to look at this question. One way is to check the progression of the team with respect to the overall records (all statistics correct until 18th June 2019).

| Decade | Matches | Won | Lost | W/L | Win% |

| 1970s | 13 | 2 | 11 | 0.181 | 15.38 |

| 1980s | 155 | 69 | 80 | 0.862 | 44.52 |

| 1990s | 257 | 122 | 120 | 1.016 | 47.47 |

| 2000s | 307 | 161 | 130 | 1.238 | 52.44 |

| 2010s | 237 | 149 | 149 | 1.960 | 62.87 |

The overall record certainly suggests so.

India were a pathetic ODI team in their early days and have seen an upward trajectory ever since. Even in the 1980s, when India won two major world tournaments, the team had more losses than wins. The team slowly climbed out of the red in the 1990s and saw an upturn in fortunes in the next decade. And in the present decade, their record is nothing short of commendable. But what if we dice the data further?

| Period | Matches | Won | Lost | W/L | Win% |

| 2000-04 | 153 | 77 | 70 | 1.100 | 50.32 |

| 2005-09 | 154 | 84 | 60 | 1.400 | 54.55 |

| 2010-14 | 136 | 83 | 45 | 1.844 | 61.03 |

| 2015-19 | 101 | 66 | 31 | 2.129 | 65.35 |

Taking a closer look at the data since 2000, some more insights emerge. The team that played under Ganguly (mostly) didn’t achieve much success overall despite a strong showing in ICC tournaments; this generation also lost a large number of finals. Under Dravid’s leadership (and later on Dhoni’s), the team’s record improved considerably and India fixed the longstanding chasing problem by discovering fantastic chasers such as Dhoni and Gambhir. And since 2010, under Dhoni and Kohli, the team has performed at another level altogether, comfortably ahead of South Africa and Australia (whose W/L ratios are ~1.7 and ~1.6 respectively). It is in this era that India made the semifinals (or better) of 4 consecutive ICC ODI tournaments, and few would bet against India making it into the top 4 in this edition as well.

What about the personnel?

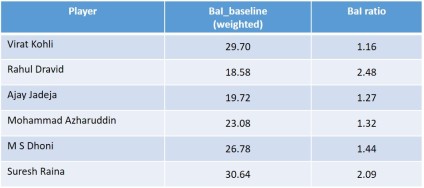

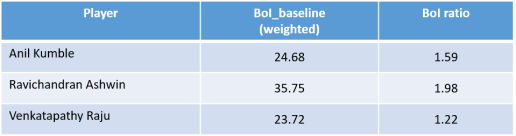

The easy way to think about it is to ask a follow-up question—how many players from this team are claimants to a spot in all-time India XI or a present-day World XI? Fielding-wise, this is without a doubt India’s best-ever side. With regard to the question posed, Rohit Sharma, Virat Kohli, and M S Dhoni are no-brainer choices. What about Jasprit Bumrah? In spite of him being relatively young, he should walk into the side—this says as much about paucity of quality Indian fast-bowling options as it does about his own ability and potential. With regard to the spin twins, it is still early days but one of them might end up with a mighty ODI record. The rest of them are fairly close as well. If one were to order Indian players on the basis of batting and bowling averages (with a 1000 run and 50 wickets cutoff respectively) to get a rough sense of players’ performances, today’s players crowd the top of the list. Only one name from an earlier era (Sachin Tendulkar, who also played briefly in this era, and Kapil Dev) feature in the top 7; even players such as Shami and Jadhav also have had good starts to their careers, as does Rayudu who didn’t find himself on the plane to England. Granted, these are still early days in today’s players’ careers, but it nonetheless does tell us the level at which they have performed so far.

But what about run inflation you ask? Do you find yourself pooh-poohing today’s batsmen since they score on flat pitches against ordinary bowlers? Where are the bowlers today in the class that earlier players had to face— Waqar Younis, Wasim Akram, Saqlain Mushtaq, Shoaib Akthar, Glenn McGrath, Brett Lee, Shane Warne, Allan Donald, Shaun Pollock, Curtly Ambrose, Courtney Walsh, Chaminda Vaas, Muthiah Muralitharan, and the others? Valid question. But also consider at the same time, today’s batsmen are feasting heavily; so shouldn’t bowlers such as Rabada, Kuldeep, Bumrah, Starc, Rashid Khan etc. get credit for doing exceptionally in today’s times? Also, one can only play against the opponents facing them. And, even if runs were “inflation adjusted”, Indian team players feature at the very top of recent statistics as well.

Another way to look at it is to ask how many players from India’s past ODI teams would walk into this squad and improve it? Sachin Tendulkar and Kapil Dev surely; Yuvraj Singh, Virender Sehwag, Anil Kumble and Zaheer Khan could be considered at their peaks, but there would be question marks about some of their fielding abilities. And after this, there is no one else. One could argue that the 2011 World Cup team possibly had equivalent batting in its era, but this was a batting unit that did well for a handful of matches (with at least 3 players dropping off after that).

Is today’s team perfect? Far from it. Though it is more well-balanced, it is still facing a philosophical battle with the present-day English team; then there are well-documented weaknesses with the new ball bowling and middle order dawdling. But probably for the first time in India’s ODI history, the team can defend a low-ish score and can win matches on the basis of bowling as well; earlier Indian teams needed insurance to close out matches as they weren’t similarly equipped.

How does this Indian team compare to the legendary West Indian and Australian teams of yesteryear? See and decide for yourself:

| Period | Matches | Won | Lost | W/L | Win% |

| WI (1973-1989) | 193 | 139 | 52 | 2.673 | 72.02 |

| Aus (1999-2008) | 281 | 205 | 61 | 3.360 | 72.95 |

The West Indies dominated ODI cricket in its infancy for nearly 2 decades (and played less than 200 matches during the time), winning 72% of the matches played. They had the best bowling attack and had a few champion batsmen as well. But the Australians around the turn of the millennium were from a different planet—they had it all: a pioneering keeper-batsman, batting depth, class-leading fielding, and miserly bowling. No wonder they dominated every team for a decade (nearly 300 matches).

Therefore, though India are the standout ODI team of the decade, they are still a few steps behind the legendary teams of ODI history. That the champion teams performed at such stratospheric heights for a decade shows what this team is up against. One also suspects that India will have to win the big tournaments consistently to remain in the memory as a champion team; after all, another exceptional team—South Africa—did well (W/L ratio of ~2 between 2005 and 2017) but couldn’t etch themselves in stone as they didn’t have any big, shiny trophy to show at the end of their reign.