The quadrennial cricketing extravaganza that is the Cricket World Cup begins in less than 48 hours when England take on South Africa. The sports pages of every news publication, online and offline are filled to the brim with stories about the players, squads and unforgettable moments of yesteryear. With excitement building up towards this grand, we decided to throw our hat into the ring with a fun exercise of our own—building a hypothetical all-time XI.

What would serve as a fair selection criteria that can be applied across the board to facilitate such an exercise in fandom? Firstly, only performances from the ODI World Cups will be considered. Secondly, the player should have played in at least 10 World Cup matches and 2 editions; this criteria is to ensure that players with a stellar showing in one tournament (for example, Shikhar Dhawan) don’t necessarily upstage players with longer, more consistent World Cup records. As a consequence of these two criteria, many players with stellar ODI records (thinking of you, Virat Kohli and Joel Garner) unfortunately miss out, but present-day players certainly have a chance to correct this in the future. The squad would nominally have 6 batsmen (2 of whom can serve as the 6th bowler), 1 wicketkeeper-batsman, 4 bowlers and 1 all-rounder but there is scope for some flexibility. With this in place, let us move on to the players themselves.

Wicketkeeper-batsman

Four wicketkeepers have stellar World Cup records: Adam Gilchrist, Kumar Sangakkara, Brendan Taylor, and Brad Haddin. Both Gilchrist and Kumar Sangakkara have had longer and more productive careers compared to the other two—hence it is down to these two. Both are excellent glovemen and hence the debate between the two will come down to batting (see below).

Top order (1-3)

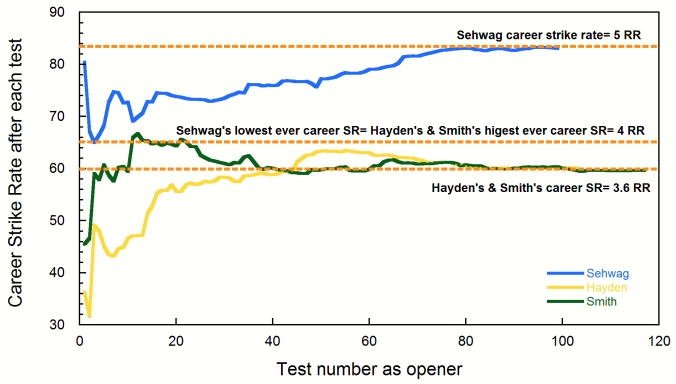

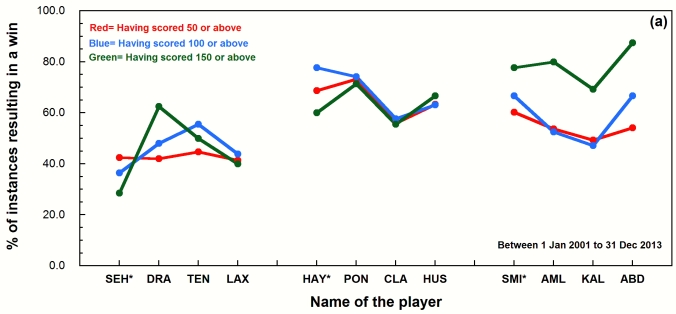

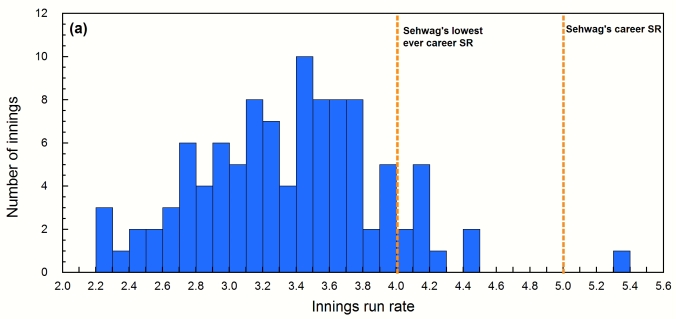

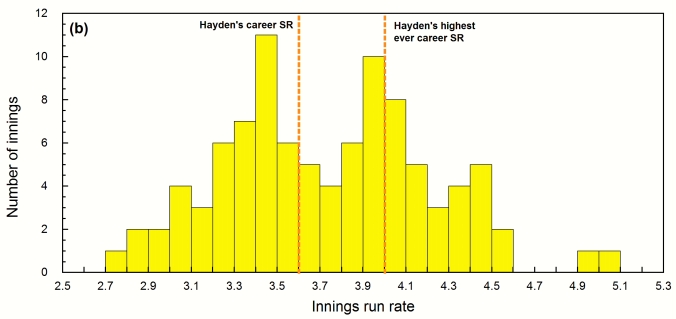

One name automatically makes the list: Sachin Tendulkar. Who can argue with the batting pitamaha’s overall record and a stellar showing in three world cups? The identity of the other two players will no doubt cause much deliberation. Will it be his illustrious batting partner, Sourav Ganguly? Or explosive southpaws such as Adam Gilchrist or Sanath Jayasuriya? We then looked at players who married consistency with strike rate at the top, leading to 4 other contenders—Mark Waugh, Herschelle Gibbs, Matthew Hayden, and Tillakaratne Dilshan. Despite Dilshan’s edge as a part-time bowler, the fact that his best performances came against the “lesser” teams put him out of contention. With little to choose between the other three, we chose Matthew Hayden for his left-handedness and higher strike rate. For the number 3 slot, Kumar Sangakkara’s consistency was hard to overlook and he easily towers over Ponting, Kallis, and Lara. A case could be made for playing both Gilchrist and Sangakkara but Hayden’s advantage (~+15 average) won the trade-off against Gilchrist’s stats (~+5 strike rate). Besides, we have packed the side with plenty of firepower in the middle order.

Hayden: 22 matches, 987 runs @51.94 avg. and 92.93 SR

Tendulkar: 45 matches, 2278 runs @ 56.95 avg. and 88.98 SR

Sangakkara: 37 matches, 1532 runs @ 56.74 avg. and 86.55 SR, 41 catches and 13 stumpings

Middle order (4-6)

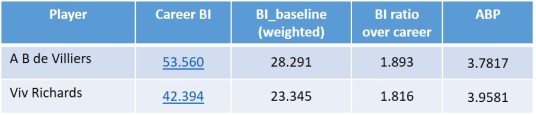

As was the case in the top order, one more name automatically makes the list at number 4: Viv Richards; his handy bowling and fielding complemented his destructive batting well. The following act is a recent-day player who probably was the closest to Richards in his pomp—A B de Villiers. The number 6 and 7 candidates are some of the hardest to fill—is it better to pick someone like Javed Miandad, or Steve Waugh, who can marshal the lower order and bring in the big hits when necessary? Ultimately, we went with flexibility and power as the top 5 have enough batting ability and consistency to stave off even the most hostile bowling attack.

Viv Richards: 23 matches, 1013 runs @ 63.31 avg. and 85.05 SR

A B de Villiers: 23 matches, 1207 runs @ 63.52 avg. and 117.29 SR

All-rounders (6-7)

There are only 4 players under consideration—Imran Khan, Kapil Dev, Yuvraj Singh, and Lance Klusener. Imran Khan has an outstanding bowling record but his batting is less than stellar. Following Viv Richards and A B de Villiers is already a difficult task and his ~66 SR would be out of place, even if it were to be “inflation-adjusted”; Lance Klusener has an amazing batting and bowling record in the World Cups and he would totally fit in in today’s T20-fuelled era; Yuvraj Singh is more a part-time bowler who had one good World Cup bowling-wise. Kapil Dev’s World Cup bowling record is merely “average” by his own lofty standards but his batting takes the cake—who can forget his immortal 175* against Zimbabwe? In the end, it is a very tough call between Kapil Dev and Imran Khan but considering that the top 5 are very consistent, we went with batting power over bowling chops. Kapil, Klusener, Richards, and Tendulkar can more than capably bowl the 5th bowler quota.

Lance Klusener: 14 matches, 372 runs @ 124 avg. and 121. 17 SR; 22 wickets @ 22.13 avg.

Kapil Dev: 26 matches, 669 runs @ 37.16 avg. and 115.14 SR; 28 wickets @ 31.85 avg.

Fast bowlers

For the fast men who will take the new ball, it is hard to look beyond two legends of the game—one known for unerring and nagging consistency, and the other, the sultan of swing. Yes, we are referring to Glenn McGrath and Wasim Akram. Unsurprisingly, they have the highest number of wickets in the World Cups (fast bowlers only). Other capable candidates such as Chaminda Vaas, Zaheer Khan, Lasith Malinga, Brett Lee, and Shane Bond miss out due to the illustrious careers of these two new ball schemers.

Wasim Akram: 38 matches, 55 wickets @ 23.83 avg.

Glenn McGrath: 39 matches, 71 wickets @18.19 avg.

Spinners

Here too, it is difficult to look beyond the two champion spinners of the game—Muttiah Muralitharan and Shane Warne. Though Warne has played only in two World Cups, his overall record pips him to the final bowling slot ahead of Vettori, Hogg, and Kumble.

Muttiah Muralitharan: 40 matches, 68 wickets @ 19.63 avg.

Shane Warne: 17 matches, 32 wickets @ 19.50 avg.

Squad balance and captaincy

Overall, the squad has it all—consistency at the top and middle, explosive power in the middle order, left-right combinations galore, a bowling quiver full of all types of arrows, lower-order batting in Akram and Warne, and even comic value in two genuine number 11s. Who will be the captain? Imran Khan would have been an obvious choice had he made it, but since we’re picking the captain after making the 11, we would pick Kapil Dev. Kapil Dev was even more crucial to India in 1983 than what Imran was to Pakistan in 1992, and he transformed a bunch of no-hopers to world champions against all odds through a mix of self-belief, inspiration, and leading from the front. Imran, on the other hand had an excellent bowling unit and decent batsmen coming up the ranks. For this reason, Kapil paaji da jawaab nahin. The cerebral Sangakkara will serve as his able deputy.

All time World-cup 11: Matthew Hayden, Sachin Tendulkar, Kumar Sangakkara (wk & vc), Viv Richards, AB de Villiers, Lance Klusener, Kapil Dev (c), Wasim Akram, Shane Warne, Muttiah Muralitharn, Glenn McGrath