We’re back to the year 2030. As discussed earlier in this series, a mysterious group of aliens have landed on Earth and are interested in facing off against the Earth’s finest in a one day international (ODI) cricket series which will seal the planet’s fate. It has now been six months since the various wise heads of the BCCI put their brains together to come up with a hypothetical batting lineup combed from ODI history to face the alien might.

Meanwhile, the aliens have gotten comfortable on Earth, and are getting to grips with its various quirks as they are going about their daily cricket practice routines. There is a lot of confusion regarding the status of the aliens—whether they are illegal immigrants or refugees—and this is occupying columns of newsprint in the West. Back home in India, the epicenter of all the action, some events are predictable and comforting. The jury is still out on demonetization. Salman Khan is still making movies, and employing a driver in the age of driverless cars. Rahul Gandhi’s latest speech is touted to be his coming-of-age moment.

The aliens are now anxious; it has taken more than six months for the BCCI to come up with half a team. The last table thumping did not have the desired effect or response from the BCCI. On their part, the BCCI are complaining about impending Presidential elections and the saga of various state associations not falling in line. Plus there is the small matter implementing the Supreme Court recommendations.

Furious at the inaction, the aliens issue yet another ultimatum, and decide to go nuclear. No, not by any means of violence; they simply choose to rewrite the various broadcasting, internet, TV and VR rights for the various India home series and the IPL. Suddenly, the BCCI wake up from their slumber and swing into action. They now huddle together in order to complete the lineup with a 15 member squad, of which only the batting lineup have been chosen so far—Tendulkar, Amla, Kohli, Richards, de Villiers, Dhoni and Klusener. This fictitious exercise is a culmination of scouring the history of ODI cricket to identify the players who outperformed their peers.

How do we go about selecting the rest of the team?

The ODI format of cricket has changed its spots over time. In the initial days of the format, teams often treated it as a truncated version of the test match. Besides, teams also had 60 overs to negotiate. With the advent of power-hitting at the start of the ODI in the early ‘90s, the game pivoted to a much more frenzied approach against the new ball. Since then, the economy rates of bowlers have been continuously on the upswing. Plus, we now have a newer format (which rewards power hitting a lot more) to contend with—the T20.

In spite of bowlers receiving a hiding over the last few years of the ODI, the basic resource dynamics of the game hasn’t changed. In the game of cricket, three basic quantities are measured—runs, balls and wickets. Depending on the format of the game, the importance of each quantity (and their interplay) varies. Considering that an ODI can be won by either bowling out the opposition or by run containment, a good bowler needs to be on top of two metrics: one, the bowling average (runs conceded per wicket), and two, the economy rate (runs conceded per over). They are the bowler’s equivalent of batting average and strike rate respectively.

The product of the two (divided by 6)—often called as the Bowling Index (BoI)—has been used by ESPNCricinfo and many others as a tool to benchmark bowlers against their peers. Usually, analysts have compared a bowler’s BoI with the corresponding BoI of the average bowler during the said player’s career—this is a method that has also been used by us in our earlier exercises. This is a solid, first-cut method no doubt, but it has some inherent disadvantages, which will be discussed and addressed shortly.

Table 1: Variation of Bowling Index (first) across the batting order in different time periods

Table 2: Variation of Bowling Index (second) across the batting order in different time periods

Upon detailed examination of the above BoI tables, some characteristics of bowling in ODIs become apparent. One, bowling in the first and second innings are totally different ball games with respect to the BoI; two, bowling at the top of the bowling order is far more advantageous with respect to bowling statistics (and hence encapsulated by the lower values of BoI).

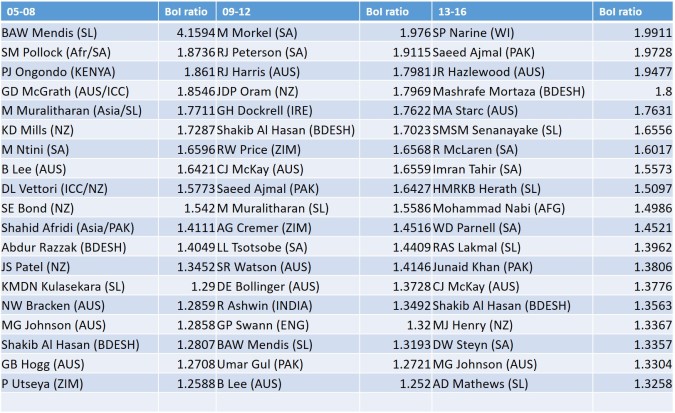

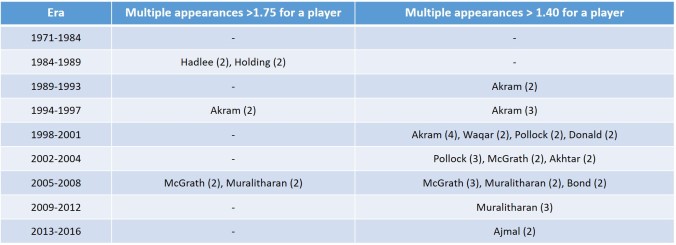

In the previous two articles of our bowling series, the BoI concept was extended in order to examine which bowlers dominated their peers in terms of their performances. We had computed and compared BoI ratios (by dividing the baseline with the BoI of a particular bowler during an era) of various players during the first and second innings of the ODI over the course of the history of the ODI (nine ODI eras in total, each having an excess of 250 matches). A benchmark (BoI ratio of 1.40) was also applied across the board (after an appropriate cutoff, of course) in order to separate the elite performers during a particular era. A BoI ratio of 1.40 represents a 40% higher performance over the average bowler. It must be noted that a BoI ratio of 1.40 is extremely rare, and less than 20 players have achieved it during every era under consideration (all stats until Dec 31, 2016 have been included).

Many bowlers have been able to perform at a very high level in some eras (Ajanta Mendis, for example), but have struggled to replicate it across multiple time periods—except for the very few standout performers who have shone throughout their careers.

Considering that the ODI has undergone a sea of change from its first sighting in 1971, a hypothetical exercise like this raises many questions. How can players from one era be compared with the present day ones? What about players—like Brad Hogg—who have had stop-start careers? Can today’s bowlers, who bowl in such impoverished times, hold a candle to the legends of yesteryear? What about the changing rules of the powerplay, influence of T20 and smaller boundaries? So many issues to resolve.

Therefore, any analysis must take all these valid questions into consideration. Hence, we have to compare bowlers’ tallies with statistics relevant to their own careers. The grandfather of ODI batting, Sachin Tendulkar, played in a record 463 matches. In contrast, the bowler with the maximum appearances in ODIs is Wasim Akram with 356—a full 107 matches lesser than the overall record. On the whole, bowlers have a lesser shelf life, and this must reflect our cutoff as well. If the batsmen had a cutoff of 75 innings at 30 runs per dismissal, the bowlers have to clear the 50 innings, 50 wickets, 2000 balls bowled at 32 runs per dismissal. At the same time, this level is moderate enough not to exclude the modern outliers. This brings a total of 132 players under the lens.

The criteria for selection would be excellence over a sustained period of ODI cricket (interested readers can go through the era-specific values in the earlier articles), unless the gulf between the BoI ratios of a bowler with a short career and a long one is hard to overlook. Considering that many present day players may not have played in as many matches, the ones who could perhaps surpass the legends (in terms of BoI ratio values) in the future will be mentioned in the special mention category. Next comes the algorithm for selection.

Table 3: Variation of BoI (second) (%) using BoI (first) as a reference. Eg. BoI (second) is % higher for 1&2 compared to BI (first) between 71-84. (BoI (second)-BoI (first) /BoI (first))*100

Upon detailed examination of the above BoI tables obtained from the first two parts of the bowling exercise, it becomes clear that this method does not take three crucial factors that affect BoI values into consideration. One is the first to second innings disparity; second is the bowling order; third is the era centric values. To some extent, a uniform baseline takes care of the third factor, but the first two lie unaddressed. Considering that the spinners have struggled to match BoI values of fast bowlers, a tweak has to be applied to make sure there is decent representation across the board. This tweak has to be based on the bowling opportunities that was provided to the bowler during his career (until 31 Dec 2016).

Are there other concepts that we could use? The Average bowling position (ABoP) is a composite number representing the mean of all the bowling positions bowled in by a particular player. While the ABoP itself cannot reveal all information (as similar magnitudes of ABoP can be obtained by differing combinations of bowling position distributions), it can give us a snapshot of a bowler’s most usual bowling position in the bowling order.

Additionally, readers must also keep in mind that the bowling order is a lot more fluid compared to the batting order. For example, it can be said with a large degree of confidence that the openers are still at the crease at when the batting team have lost no wickets (barring rare cases of a batsman retiring hurt). However, a bowler can open the bowling, bowl the solitary over, and then complete his quota at the death; but the scorecard will still list his bowling position as 1. See the problem? Unfortunately, ball by ball data is not available for matches before 2001, and hence we will have to resort to the bowling order.

Using the same principle of the ABoP, the fraction of innings bowled in the first/second innings, in different bowling positions and in different time periods will be multiplied with the respective BoI values of all bowlers who bowled in similar circumstances (tables 1 and 2), which is then summed up to get the bowler’s BoI baseline (weighted) for that particular player. In some way, with this tweak, we will be comparing the said player’s BoI with a hypothetical, composite, average bowler—who has been afforded similar bowling opportunities (first/second innings, bowling position and era) during the player’s career.

Now that we have nailed down the algorithm for selection, we can move on to the selection of the players.

The bowling lineup should contain fantastic strike bowlers, with the inclusions for variety and part-time options as well. Considering that the batting lineup had Tendulkar and Richards, they can be expected to fill in the sixth bowler’s role in case one of the five receive a hiding from the aliens. The fifth bowler should ideally be an all-rounder who can bowl their full quota of overs (pace or spin) and is a competent batsman, in order to lend balance to the team. The batting exercise selected seven players (one batting all-rounder, one keeper and two sixth bowlers). In the remaining eight places, we can thus select three pacers, two all-rounders, two spinners and a spare player. Additionally, a left-arm pacer and a wrist spinner would be nice as well in the interest of variety.

The metronome Glenn McGrath will be opening the bowling for the earthlings (note that players bowling at position 1 and 2 have been allocated a bowling position of 2). His BoI ratio stands apart compared to other opening bowlers such as Bond, Pollock, Ambrose and Hadlee. At the other end, Wasim Akram would be steaming in with his left arm swingers. Readers must note that in his young, 59 match career (until 2016), Mitchell Starc has racked up some ridiculous numbers. Considering that he has had a stellar 2017 as well, it might be wise to succumb to temptation and select him instead. Though, does Akram’s excellence at the death and the many headlining moments over 356 matches shade the younger man’s career so far? Really tough call.

In the first change position is the all-time BoI ratio leader—Joel Garner. The extent to which the man towered over the rest (both literally and figuratively) can be gauged by the fact that no one else got close within ~8% of his career BoI ratio. Other fast bowlers (with illustrious colleagues) like Holding, Donald and Morkel also have excellent values in spite of bowling at no. 3. Perhaps, in any other team, they might have opened the bowling.

In the earlier method of comparing the player’s BoI with a flat baseline, spinners had poor representation. However, with this new method in place, their numbers are quite impressive in the overall scheme of things. Leading the tweakers’ pack is Saeed Ajmal, but given his history with his bowling action, Muralitharan will be chosen lead spinner. Saqlain Mushtaq is not far behind as well. In the case of wrist spinners, Imran Tahir (62 matches) has clearly outperformed his peers but would he walk into the side ahead of Shane Warne (194 matches)? Yet another case of Starc vs Akram.

What about the multi-taskers? Though part-timers like Allan Border and Darren Lehmann have great statistics (Lehmann doesn’t clear the 2000 ball cutoff), their ABoPs is close to six and hence they were only capable sixth bowlers—clearly not good enough to merit selection. In our team, all-rounders with more credible bowling abilities have been chosen.

Andrew Flintoff takes the pride of place amongst the bowling all-rounder pack—his batting numbers are pretty good as well. Klusener, Watson, Imran Khan, Kallis and Kapil Dev were better than their weighted baselines over their careers as well. Among the spin bowling all-rounders, Shakib Al Hasan is the undisputed leader with impressive bowling numbers; that he’s been able to post such statistics despite hailing from a weaker team is indeed commendable; him being a left-arm spinner adds to the variety as well. The presence of all-rounders adds a lot of depth to the team—the overall sum of the batting index (BI) ratio and bowling index (BoI) ratio gives an indication of their average contribution per match compared to the average batsman/bowler. Klusener is the overall leader due to his batting tilt; Flintoff and Shakib are very capable bowlers and they complete our set.

All that is left is the identity of the 15th player.

Is there enough cover for the pacers with only 3 frontline quicks? Should it be Holding, a pure pacer, or someone like Pollock who has a near-identical BoI ratio but can bat really well? Considering Flintoff is a super bowler in his own right, another pacer seems excessive. What about bolstering the middle order? Where is the left handed batsman? How can someone like Bevan or Hussey miss out with such high BI ratios? Not that it is any consolation, but Shakib Al Hasan is a decent batsman (though not in the same class); also—though he might not like it—Sachin Tendulkar could perhaps be persuaded to bat in the middle order if push came to shove. Shane Watson could also be considered as a batting pick due to his flexibility, but he wouldn’t displace any batsman on batting merit.

Considering all this, our BCCI’s last pick would be the left handed Adam Gilchrist—with a BI ratio better than Hayden (and close enough to the right handed Greenidge and Sehwag). What tipped the scales in his favour was his handedness, firepower (which could perhaps be deployed in the lower order as well) and his keeping ability. Yes I do hear that AB de Villiers has kept wicket in ~28% of his matches, but we wouldn’t want to burden the star batsman with additional responsibility given that the fate of the earth is at stake, would we?

This team has it all—thrilling openers, chase-meisters, finishers par extraordinaire, red-hot pacers, cunning spinners and multi-taskers supreme. Regardless of the nature of the pitch and the opposition, this squad should find the relevant answers; though, if the otherworldly beings turn out to be multi-limbed, irregular-formed, squiggly beings, I suspect the issue of handedness and leg before wicket will cause much consternation in the commentary box. The uber-cool, unflappable Dhoni would be captain of the side.

Bring on the aliens.

World XV: Tendulkar, Amla, Gilchrist, Kohli, Richards, de Villiers, Dhoni (c & wk), Shakib, Klusener, Flintoff, Warne, Murali, Akram, McGrath, Garner

Honourable mentions who could make it to the team in the future if they continue to perform at similar levels for a few more years: Buttler, Starc, Tahir