Ace of the chase: Not another ODI series goes by without an ODI chase masterclass. Image source: 1.

Yet another ODI series, yet another successful Indian run chase punctuated by a Kohli hundred. Tall target? No problem – few swishes of the bat produce flicks racing to the boundary, keeping the asking rate in check. Pitched outside off stump? No problem – a succession of crisp cover drives to bring the crowd alive. What can you throw at me, he asks. Oh, by the way, he can also buzz around with a flurry of tapped singled on either side of the wicket. Ace the chase, bow to the crowd and spiel template answers at the presentation party. Ho-hum, this is all so humdrum. Virat “King” Kohli turned 28 yesterday. Twenty eight! He’s yet to reach the peak years of a batsman. The mind boggles at the feats he might conjure in the years to come.

With every passing ODI series, the legend of Virat Kohli only grows louder. It is not just his game that sticks out; his demeanour on and off the field shows a strain of confidence that is very different from the ones displayed by his predecessors. Tendulkar would quietly nod and hold his pose while going about his business. The affable bunch of South Indian gentlemen from the turn of the millennium would mostly be celebrating within themselves lest they offend the opposition. What about Ganguly, you ask? He would strut around by puffing his chest, but it was mostly after the match had been duly won.

This thumbing-my-nose-in-your-face attitude was different. The upstarts from the 2007 T20 World cup had shown that they could rile and wind up even the most seasoned, hard-nosed Aussie. Virat Kohli only took it further by showing his finely developed vocabulary (which would not be out of place in an R-rated Hollywood gangster movie) as he led the U-19 India side to World cup title.

Over these last few years, Kohli has no doubt shed the baby fat. He has learnt to tone down the foul mouth in the recent past – so much so that parents don’t have to reflexively reach out for the remote anymore when he scores a hundred. He has also racked up some ridiculous numbers in the ODI format.

Coming in at number 4 in the test team with an MRF bat in hand, to wild cheers and chants from the crowd, this association with a legend of the game is not merely subliminal. Can the topic of blasphemy be finally broached? Is this formerly-potty-mouthed-now-cleaned-up act comparable to the man who was anointed as God? Gasp!

Spot the difference: TV feed grab showing the similarities between Tendulkar and Kohli. Image source: 2.

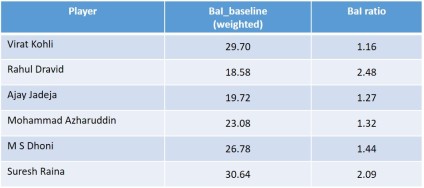

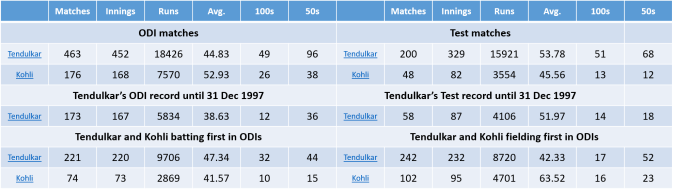

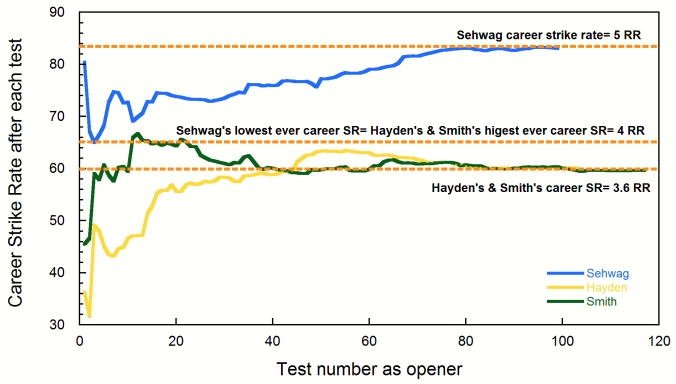

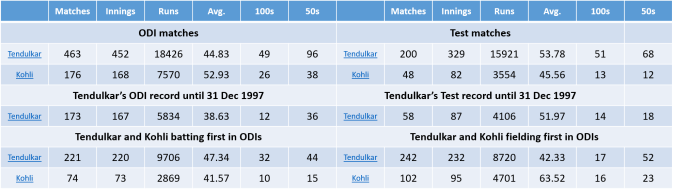

Before embarking on his annus mirabilis in 1998 (where he scored 1894 ODI runs in 33 innings), Tendulkar had clocked 173 matches (167 innings). As of 29th October 2016 (India has finished its ODI quota for 2016), Virat Kohli has played in 176 matches (168 innings). Virat Kohli’s ODI record at this similar juncture is far ahead of Tendulkar’s – and this advantage holds even if the latter’s 1998 exploits are included. Tendulkar’s overall ODI record is surely under threat from Virat Kohli’s insatiable appetite.

The test matches are a different story though; Kohli is yet to come close to Tendulkar’s individual record at a similar stage. More importantly, Tendulkar had already distinguished himself with at least one exceptional innings in each overseas tour; Kohli has fulfilled it partially and will surely get his chance to correct it in the years to come.

Table 1: Comparision of Tendulkar’s and Kohli’s careers at similar vantage points.

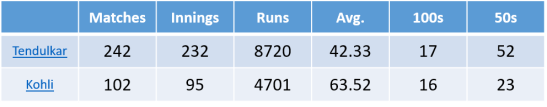

In the ODI game too, Kohli and Tendulkar differ in the manner of their records. Tendulkar had a slight preference in batting first and setting up the game. Kohli, as we all know, relishes the chase a lot more, and scores 50% more runs per dismissal while batting second. Kohli’s record while batting first is very good but he’s a victim of his own high standards. Unsurprisingly, the go-to image associated with Kohli is one of a batsman bossing the chase. And every time the Indian team fails to finish a Kohli special, the mind goes back to Tendulkar and the Indian team of the 90s.

What about Tendulkar and chasing?

You think I’m joking, right?

Scenes from a memory: Tendulkar’s many classics in a chase. Images sources: 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8.

Sharjah in 1998, 117* in the 2008 CB series, 98 against Pakistan in the World cup are few famous triumphs associated with him. He dazzled with his 175 at Hyderabad, his 65 at Kolkata and his 90 at Mumbai but fell short of the target in varying degrees. He didn’t get going either in the two World Cup finals or the NatWest final.

Why is our perception of Tendulkar chasing intertwined to him not performing under “pressure”? Why is not finishing the job (unlike Kohli) Tendulkar’s albatross? I’m now going to uncomfortable territory with this argument – We know Kohli is good but was Tendulkar any good at all while chasing?

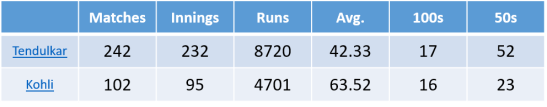

Table 2: Comparision of Tendulkar’s and Kohli’s overall chasing records in ODIs. Kohli seems far ahead of Tendulkar in conventional metrics.

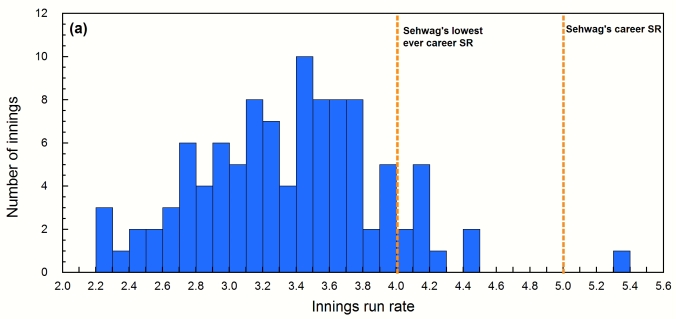

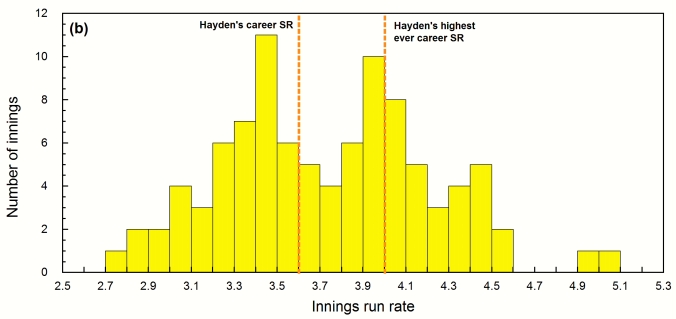

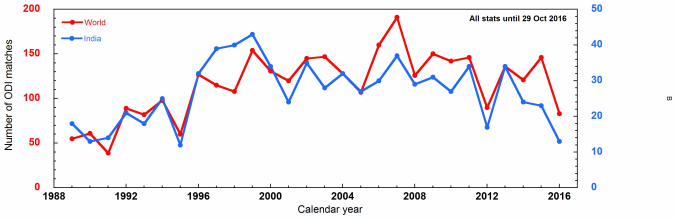

At first glance, comparing Kohli’s chasing record vis-à-vis Tendulkar’s seems like a no-contest. However, we must remember that ODI cricket has changed a lot since Tendulkar’s debut in 1989. For starters, it hadn’t made up its mind about the duration of the match, coloured clothing, third umpire, choice of lighting, fielding restrictions, resolution of weather affected matches or the colour of the ball(s). Hence, it is important to examine records as the ODI format evolved. Here, we will proceed to examine calendar year trends from 1 Jan 1989 (year of Sachin’s debut) through 29 October 2016 (India’s last match for 2016).

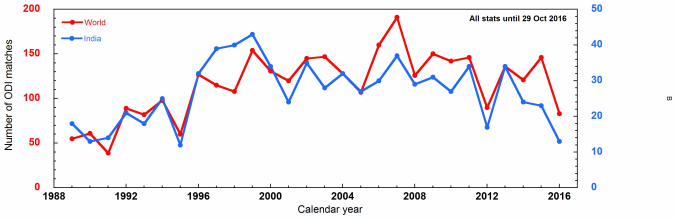

ODI calendar: The number of ODI matches played by all teams (red) and India (blue) every calendar year since 1989.

The number of ODI matches per year have steadily increased from 1996 till they reached a peak in 2007. The World cup years have seen a local maximum in terms of matches and the year following a World Cup has seen a significantly lesser number. Since the inaugural T20 world cup in 2007, the number of ODIs have been steady (close to 1999- 2004 levels). The Indian scheduling has largely followed worldwide trends except for a few anomalies.

Table 3: Number of ODI matches played in the segmented time periods.

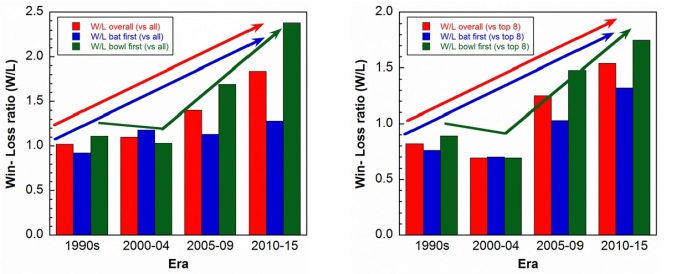

For this article, time periods have been segmented into four year slices (mostly). Each slice has at least 40 matches where India has chased and also features a World cup. Kohli made his debut in 2008 and batted twice in Indian chases in the 05-08 time period and his record in that era can be ignored. The last two time periods represent how Kohli has batted with and without Tendulkar in the Indian ODI team mix.

The first slice is five years long and this choice is pretty deliberate. It was that match in Eden Park in 1994 when Tendulkar opened for the very first time (instead of Sidhu, who was injured) and brutalized New Zealand en-route to 82 from 49 balls. The 1996 World cup clearly benefitted India as a team and it discovered its cash cow during the tournament. It was in this setting that the genius of Sachin Tendulkar was beamed via satellite TV to millions of Indian homes.

It was the ODI format which made the legend of Sachin Tendulkar in the 90s; India were largely pedestrian in test cricket until then with isolated periods of excellence. In the test format, a good team batting performance usually only prevents a loss but a good team bowling performance almost always results in a win. Without match winning bowlers, India often came short in test matches as they struggled to capture 20 wickets.

The ODI template is not cut from the same cloth though; it is enough to score enough runs and focus on run containment alone (as opposed to test cricket where the opposition has to be bundled in addition to run containment out for win). Hence, a batsman plays a match winning role more often in ODIs and a team can afford to be successful without a great bowling attack.

Table 4: Overall chasing trends for ODIs from 1 Jan 1989 to 29 Oct 2016.

Looking at the upheaval of the ODI game over the last 28 years, several trends appear. Batting positions 1-4 are still the best place to bat in ODIs – the players get to play >40 balls/ dismissal, ~20% of the innings result in a big score (50s and 100s) and over 2% of the innings result in 100s. The possibility of staying not-out for an opening batsman is pretty slim (~1 in 14 innings). Batting down the order in a chase increases the odds to ~1 in 8 innings for No.3 and ~1 in 5 innings from No.4 onwards. All things considered, in terms of runs/ dismissal, balls/ dismissal, NO% and big score% – the best place to bat in an ODI chase is at Nos. 3 and 4.

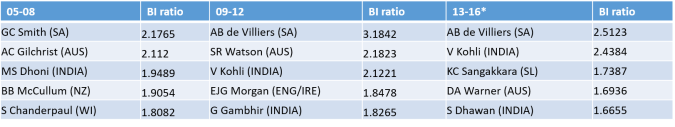

What might be a good metric to benchmark batting strength? Two simple metrics come to mind, namely, the runs per dismissal (batting average) and the strike rate (runs/ 100 balls). The product of the two divided by hundred, called the Batting Index (BI), is an intuitive measure of the contribution of a batsman. Since the primary job of a batsman in a chase is to score runs at a particular clip in pursuit of a target, runs, balls and dismissals are equally important. This measure (BI) encompasses all this information and has been used in stats analysis on various websites. A ratio of batting indices with respect to the baseline gives an idea of how far batsmen were ahead of the field at the time. Only statistics from the second innings were used in generating the baseline.

Table 5: Variation of Batting Index (chasing) across the batting order at different time periods.

The above table gives a good indication of how ODI chasing has changed over the years. At the start of Tendulkar’s career, the middle order (particularly no. 4) was the best place to bat. The baseline has somewhat flattened out from Nos. 1-5, probably due to reasons discussed previously. In the last four years, No. 3 has been the best place to bat.

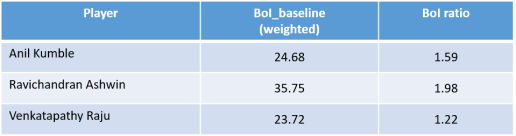

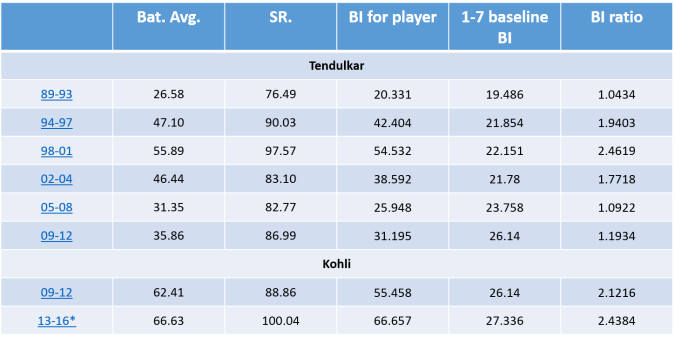

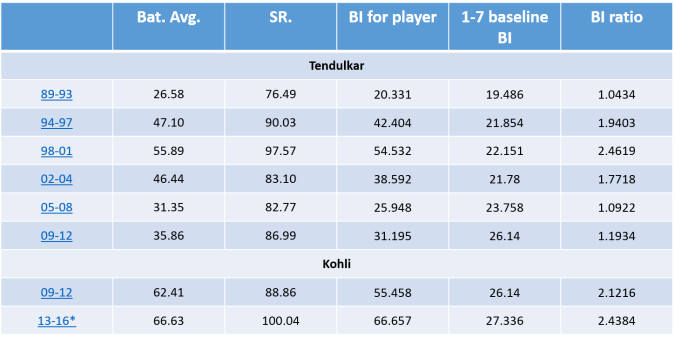

Table 7: BI ratios for Tendulkar and Kohli (in chases) at different points of time during their career. Kohli’s 05-08 record has not been shown since he played only 2 matches

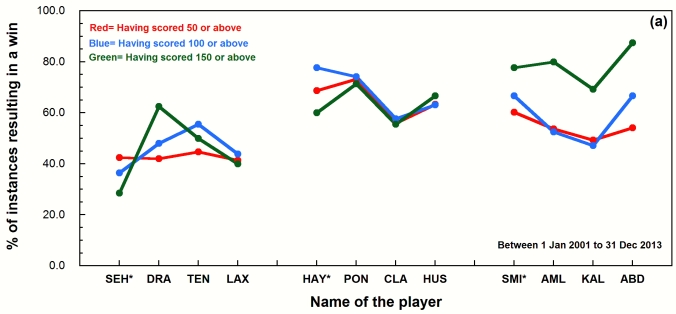

Looking at the BI ratio, it is fair to say that Tendulkar was an average middle order chasing batsman early on in his career. The middle order stint didn’t help him in piling on big numbers. The move to the opening slot was inspired and how! Tendulkar performed at least 77% higher than an average (1-7) batsman while chasing between 1994 and 2004. Eleven freaking years. Take that in for a moment. Kohli has racked up similar impressive numbers over the last 8 years and his peak is just marginally lower than Tendulkar’s peak.

Table 8: A look batsmen with top BI ratios (chasing), across time periods. A cutoff of 500 runs (pre-89)/ 750 runs (post-89) was applied. Tendulkar performed at a level close to the batsman with the best BI ratio for 11 years between 1994 and 2004.

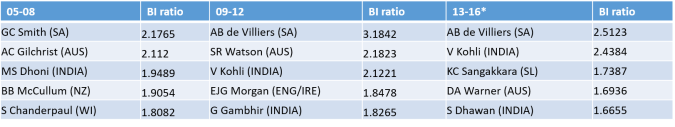

But how much did these wonderful batsmen dominate the world? For this, we need to look at the entire field. The field comprises a list of batsman (who batted between 1-7 in a run chase) who scored a 500 runs (pre-89)/ 750 runs (post-89), ordered by BI ratio. The minimum runs bar was chosen in accordance with the total number of ODI matches played in a particular time period.

Table 9: Batsmen with the best BI ratio (chasing stats only) between 1994 to 2004. Tendulkar is the only batsman to make it to the top 5 in all three time periods.

Tendulkar was the top chasing batsman between 98-01 and performed 20% higher than the second highest BI ratio batsman in that time period. He was also in the top 5 in the adjacent time periods and was not far-off from the top batsman. He and Gilchrist are the only two players who have BI ratios of more than 1.75 over 3 time periods.

Table 10: Batsmen with the best BI ratio (chasing stats only) between 2005 to 29 Oct 2016. Kohli is within the top 3 over the last 8 years, with de Villiers ahead of him in both time periods. Dhoni, Gambhir and Dhawan have been batsmen with top class BI ratios as well.

Kohli has been unbelievable, no doubt. But he happens to inhabit the same time period as AB de Villiers, who has made a mockery of chases over the last 8 years. AB was far ahead of the chasing pack between 09-12 but Virat’s chasing BI ratio is quite close to AB’s over the last 4 years.

What about India’s poor chasing record during the 1990s then? Despite popular perception, it wasn’t all rosy during Ganguly’s tenure. In fact, it must be noted that the chasing “monkey” was finally off India’s back only in 2005. India exorcised its chasing demons during the contentious Greg Chappell-Rahul Dravid era when they won 17 matches on the trot while chasing.

Since it has been established that an opening batsman is not out ~7% of the time, an opening batsman can only set up a chase and not finish it ~92% of the time (Fun fact: Tendulkar was not out as an opener in a chase ~11% of the time during his world beating 94-04 years). Invariably, the responsibility of shepherding a team to its target falls on the Nos. 3-5 batsmen. Kohli’s chasing prowess presents itself in the statistics. What about Tendulkar then? Can Kohli be compared to Tendulkar of the 1990s?

ODI giants in our midst: The time periods of Indian players who have scored at least 5000 runs in ODIs. Only the time period for which they were regulars in the team was considered (at least 10 ODI matches/ year at the start or end of their careers).

The answer to this question lies in how Indian players have performed in a run chase. Since 1 Jan 1989, 12 Indian players have amassed 5000 ODI runs and can each stake a claim in India’s all-time ODI squad. The very same players have also racked up 2000 runs each while chasing. Tendulkar has the unique distinction of having played with all of them.

The same BI ratio metric can be used to get a list of top players in each era (at least 500/750 runs while chasing). A cut-off of BI ratio of 1.4 can be applied to separate the really elite players from the rest. It must be noted that maintaining this 1.4 level over a long period of time is extremely rare and only 4 players have achieved this in chases over three time periods – Lara, Tendulkar, Gilchrist and Dhoni.

Table 11: A snapshot of India’s chasing strength over the years. Of late, India has had at least 3 batsmen with BI ratio > 1.4. During Tendulkar’s best period, he could not hail upon similar support.

Depending on the time period, there are 9-17 players who have cleared this bar. A BI ratio of 1.4 implies that the particular batsman has batted at 40% better than a regular batsman. If a team has 3 of them, it implies that they have, in effect, got an extra batsman (with respect to the baseline) in the chase.

The above table contains the answer to India’s chasing woes during Tendulkar’s peak chasing years. Only Ganguly and Sehwag made the cut as top class chasers during Tendulkar’s peak, that too for one time period. At his absolute peak between 1998-2001, he was all alone; and, he had to contend with a lot of chopping and changing across the batting order – 40 players tried out for 7 slots. ODI teams also faced more high quality bowling those days – Waqar, Wasim, Saqlain, Akthar, Mc Grath, Lee, Warne, Donald, Pollock, Ntini, Ambrose, Walsh, Vaas, Murali and the rest. It was no wonder that the Indian chase collapsed with Tendulkar’s wicket in those times. Unfortunately, Sachin didn’t have much to show for during those 11 years since his team let him down most of the time.

On the other hand, Kohli has always batted in the company of other batsmen who were competent in a run chase. In fact, Gambhir in 05-08 and Rohit Sharma in 13-16 just missed the cut with BI ratios of 1.3. That Kohli has achieved his batting feats with the security of a settled, great batting line-up, against lesser quality bowlers does not belittle his record by any means; he still had to strive hard to make those runs. We must also not forget that Kohli rarely played against teams like Zimbabwe, Kenya, Ireland or Namibia.

It follows that Kohli’s dismissal in a chase, however devastating, has not such a deathblow in a manner of Tendulkar’s dismissal in those 11 years. His true test will be how he bats without the cushion of additional support, like Tendulkar did until 2004. It will probably happen when MS Dhoni retires.

Can Kohli be compared to Tendulkar with this evidence? I would say that every player should only be judged at the end of their career. But pushed for an answer, I would say that regardless of what happens in the future, Kohli has demonstrated world-beating ODI chase credentials and has performed at Sachin’s peak chasing level (the worse part of his record) for 8 years. And then there is the small matter of the other part of Sachin’s record – his better ODI first innings stats and his test statistics.

There is still quite a bit that the king must do to before he can be canonized as God.

Miles to go before I sleep: Kohli paying his respects to Tendulkar during the 2016 T20 World cup. Image source: 9.

Disclaimer: Some images used in this article are not property of this blog. The copyright, if any, rests with the respective owners.