In a few days, India will begin their World Cup campaign against South Africa. On paper, India are one of the stronger sides coming into the big tournament and will look to add a third world title to their kitty. Barring a major debacle, India should finish in the top 4 and make it to the semifinals; and after that, it is a matter of two good knockout matches for any team looking to lift the title and make cricketing history.

Throughout India’s ODI world cup history, several illustrious players have served the Indian team well, bringing honour and distinction in the process. But who are the Indian players who have lit the world stage = at cricket’s biggest tournament? Are they the usual suspects such as Tendulkar, Kapil Dev, Dhoni, Virat Kohli (who are sure-shot walk-ins for an all-time India ODI XI), or are there other unexpected players who have shone? In order to investigate this, we will undertake an analytical exercise to identify the players who have performed at a high level in the World Cup.

First up, some ground rules. Only world cup performances will be considered (with an 8 match and 2 tournament cutoff). This criterion ensures that players don’t just make it on the basis of a few good weeks, but rather that their good performances were spread out over multiple tournaments, thus rewarding long-term consistency.

What might be a good metric to measure ODI performance? Over the years, we have preferred to use (as have others) Batting and Bowling Index ratios (BaI ratio and BoI ratio respectively) to get a sense of the “level” at which a player operated in the period under consideration. Analysts have traditionally multiplied a player’s average and strike rate (economy rate for bowling) and divided it by a baseline to get a ratio that represents how valuable that player was. While this is a good start, it has some limitations. Hence, we have tweaked this to take into consideration run-inflation over the years and position in the batting/bowling order as different players have faced different conditions and circumstances throughout ODI history. So, the baseline of a player is derived based on weighting the number of matches played in a particular World cup edition and at a particular position—the rationale being, it is fairer to compare a player with his counterparts rather than everyone in the batting/bowling order. With this tweak in place, a player’s performances are largely compared to those of a hypothetical, composite player who faced similar opportunities.

Now that we have defined the criteria, let us have a look at how the players have performed with respect to their baselines.

At the top of the order, the peerless Sachin Tendulkar leads the pack having performed at a level that was ~2 times that of the hypothetical average player who got the same batting opportunities during his era. His partner-in-crime, Sourav Ganguly isn’t far off with a BaI ratio of 1.94. Considering that these players played in multiple world cups, this is an exceptional record. The Nawab of Najafgarh has performed at a high level as well, with Sidhu rounding up the top 4. The current openers Rohit Sharma and Shikhar Dhawan (who didn’t make the cut due to the 2 tournament cutoff) could break into this list with a decent showing in the upcoming world cup.

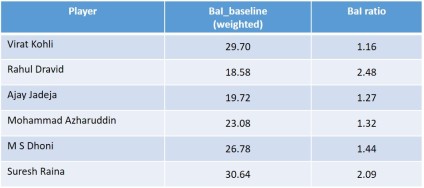

The middle order springs a few surprises. Virat Kohli may have game-leading ODI statistics at the moment, but he is yet to produce his best at the World Cup. His level is only at 1.16 times the average player—of course, the presence of other illustrious peers in the top order hasn’t helped his cause. Rahul Dravid is easily India’s most valuable batsman from the BaI ratio perspective due to his stellar showing at multiple world cups (and he kept wicket in many games as well). Middle-order stars from more than 20 years ago—Azhar and Jadeja—have also performed respectably for India. M S Dhoni, in his World cup matches, hasn’t hit the heights of his otherwise superlative career but still has played at a very good level; but to be honest, there was no other wicketkeeping contender apart from Dravid. Suresh Raina shows the opposite characteristic of Kohli—he may not have extraordinary stats in ODIs but his showing in the World cup has indeed been very good with respect to his peers.

Now come the multi-dimensional players with two strings to their bow—the all-rounders. If single-skill cricketers could only contribute in one way, an all-rounder’s contribution is effectively the sum of batting and bowling contributions, making them extremely valuable to the team.

Batting-wise, Kapil Dev has been class-leading but his bowling has been rather ordinary at the World Cups. On the back of his impressive showing at the victorious 2011 World Cup campaign, Yuvraj Singh has extremely high numbers both in the bowling and batting departments, and he easily makes the cut along with Kapil. The heroes of the 1983 World Cup, Mohinder Amarnath and Madan Lal have slightly contrasting stories to tell with respect to statistics. According to the methodology, Madan Lal has the highest sum and there is no doubting his bowling contributions; but truth be told, this is an anomaly resulting largely because of his batting numbers racked up from low batting positions. In Amarnath’s case, even though his contributions were very valuable in the latter stages of the 1983 campaign, in the overall World Cup picture, they weren’t path-breaking.

Among the pace battery of the 2003 World Cup team, left arm quicks Ashish Nehra and Zaheer Khan edge the senior partner and mentor Srinath in the BoI ratio stakes. Dovetailing with Kapil Dev, this should be a good pace attack on the whole. The man who was blessed with banana swing, Manoj Prabhakar, has also performed at an acceptable level for India. But apart from these 4 (and Kapil), it is slim pickings (Shami and Umesh Yadav did well in 2015 but didn’t qualify due to the criteria). But this might change very soon—one suspects that a couple of fast bowlers from this tournament will break into this list soon.

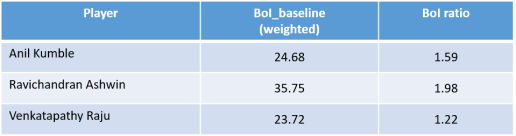

Rounding up the team are spinners from south India. Though they weren’t necessarily first-choice throughout their careers, Kumble and Ashwin are the top spin bowlers for India according to BoI ratio. Beyond these 2, there is daylight and then Venkatapathy Raju. What about long-serving Harbhajan Singh? Surprisingly, he has very ordinary numbers in the World Cup.

Now that the analysis has revealed the “value” of each player, who makes the final squad? 10 out of 11 places are automatic picks; the odd one out is the solitary middle order slot. Suresh Raina made his runs over 9 innings; now compare this to Sehwag’s (22) and Azhar’s (25) match tallies. Though all 3 satisfy the selection criteria, Suresh Raina has played far fewer matches for his returns and hence he has to unfortunately sit this one out. So do we ask Sehwag to bat at 3? Or do we go with Azhar’s experience at 4? We prefer the latter. Among all the amazing options, we pick Dhoni to captain this fantasy XI.

All-time India World Cup XI: Sachin Tendulkar, Sourav Ganguly, Rahul Dravid, Mohammad Azharuddin, Yuvraj Singh, M S Dhoni (c & wk), Kapil Dev, Ravichandran Ashwin, Anil Kumble, Zaheer Khan, Ashish Nehra