In late 2003, the Indian U19 team won the Asia under-19 final versus Sri Lanka in Lahore. A certain bowler grabbed three wickets in the final, thus skittling the Lankans for a low score. In fact, this wasn’t his most eye-catching performance during the tournament; he had nabbed nine wickets against Bangladesh.

No, the earlier sentence wasn’t a typo. He outwitted nine batsmen in seven overs and change. That too, in an ODI. In the entire tournament, his wicket tally was nearly three times compared to the second guy. He was a handy batsman too; he had scored 94 runs over 3 dismissed innings. One more decent performance in a Ranji match, and he was on the plane to Australia to play in the 2003-04 tour.

Sultan of swing: Irfan Pathan had an impressive beginning with the Indian team. Image source:1.

In case you hadn’t guessed the protagonist, it was Irfan Pathan. Yes, the same banana-swing-hattrick-hero-pinch-hitter-WorldT20 final MoM-I’ve-regained-my-swing-jhalak-dikhla-jaa-contestant Irfan Pathan. Just when India seemed to get a bowler who could also bat, he seamed and swung no more. A nation which had held its breath in anticipation suddenly exhaled, expressing a collective sigh of yearning.

India had been there before. Agarkar had scored a hundred at Lord’s, India’s fastest ODI fifty, and had gotten to 50 ODI wickets faster than anyone else (stop rolling your eyes). But one tour to Australia had answered the primordial question of which had come first—both the duck and the egg came together when Agarkar was at the crease.

Similarly, an over-enthusiastic commentator had just about invoked a comparision when Laxmi Ratan Shukla bowled his first ever delivery at the international stage. It was a no-ball.

Kapil Dev had spoilt the nation.

The man for all seasons: Kapil Dev was India’s greatest fast bowler, and a more than handy batsman. Image source: 2.

Kapil Dev was a man who could bowl faster than his run-up; he was a man who could score 175, coming in at 9 for 4; few steps for the man (to catch Richards) was a giant leap for India’s 1983 World cup fluke victorious campaign; he could out-swing England in England; and, smash four sixes in four balls to avert the follow on. In short, Kapil Dev da jawab nahin.

Where the hell was India’s next all-rounder?

Around the same time period that Irfan Pathan was confounding batsmen in Australia, a middle-order batsman took guard at the Chinnaswamy stadium in an under-17 Asia cricket council match in the January of 2004. He would score only four runs, and get dropped in the next match in favour of a young Mumbai batsman—Rohit Sharma.

Fast-forward to 2011, this middle order batsman would make his debut against the West Indies, with Rohit Sharma having to wait on the fringes. He would go on to score his first hundred in only his third match, providing a consolation to the Wankhede crowd who had turned up anticipating Tendulkar’s 100th century (he was out for 94). Oh, he also snared 22 wickets during the series under trying circumstances, by the way—India having conceded the lead twice—en route to being awarded the Man of the Series.

Given how things had turned out in the past, it was perfectly understandable that Indian fans were cautious before making the big proclamation. Me? I was just happy that our off-spinner had grabbed us some wickets.

All round mastery: Ashwin has been India’s go-to allrounder over the last 20 months. Image sources: 3 & 4.

Perched firmly at the top of the ICC bowler and all-rounder rankings, it is fair to say that Ashwin has gone from strength to strength over the last 20 months. Is it time to label him as an all-rounder? But what does it mean to be an all-rounder in test cricket? How does Ashwin compare to his illustrious predecessors? Do all all-rounders fulfil the same role? What do the stats say? All stats in this article are from before the first India-Australia test.

In the game of test cricket, the possession of the all-rounder is a highly coveted, yet elusive one. There are only a handful of individuals who have claimed significant levels of mastery over two skill sets, namely batting and bowling. Loosely, an all-rounder is defined as someone who can bat in the top six, and can contribute as a match-winning bowler.

The often quoted gold standard demonstration of all-round skills is the 1981 Ashes (famously dubbed Botham’s Ashes), where Ian Botham topped both the batting and bowling charts for England with 399 runs and 34 wickets. In terms of long term excellence, there isn’t a finer example than Imran Khan averaging over 50 with the bat and under 20 with the ball over the course of 52 matches spanning a decade. Normally, either one of the statistical measures would be sufficient for world-class pedigree, leave alone two. For what it’s worth, Ashwin had measures of >43 and <24 respectively in 2016. Baby steps, still.

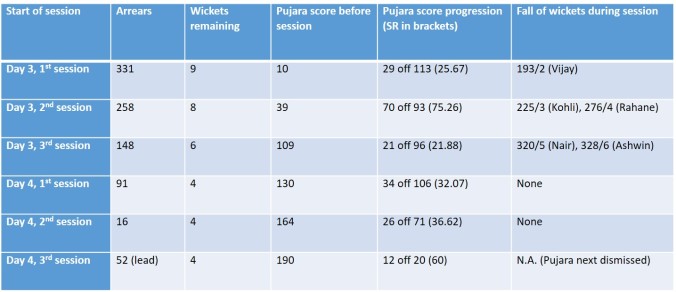

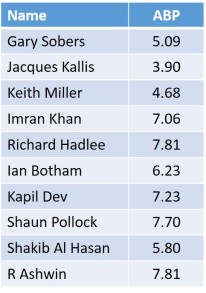

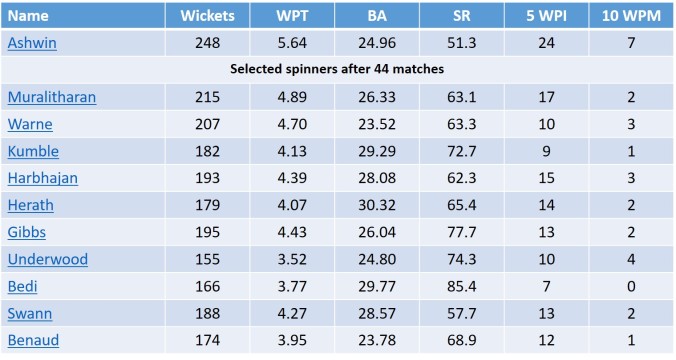

Over the history of test cricket, only a handful of players have been bracketed as all-rounders. The above list contains some of the most famous names of the sport. All the above players have crossed a certain minimum threshold: 45 test matches, 2500 runs, 150 wickets and a positive average difference. Unfortunately, for various reasons, I had to leave out some illustrious names such as Aubrey Faulkner, Tony Greig, Richie Benaud, Chris Cairns, Vinoo Mankad and others. Over the course of this article, we will be taking a close look at Ashwin’s career progression and team role, vis-à-vis his counterparts.

A good way to capture the career progression would be to look at the real time advancement of various cricketing metrics. A note of caution, though: since these are real-time, cumulative figures, the perturbations later in the career would be much smaller due to the benefit of a larger cushion. A simplistic example to illustrate this point would be to state that 1 month is 8.33% of a 1-year old’s lifetime, but is only ~0.5% of a 16-year old. Hence, due to the “streaky” nature of early career statistics, the values from the first 10 innings/tests have not been represented (but have been included) in some graphs (these have been clearly mentioned under each figure caption).

In most graphs, for the sake of easier visualization, the data has been represented in a split-window approach of two graphs side by side, each containing the data of five players; the data points of each player have been colour coded as per traditional national team jersey colours of the shorter formats.

First up, would be various measures of batting ability. In the test format, batsmen are measured by their run-making contribution.

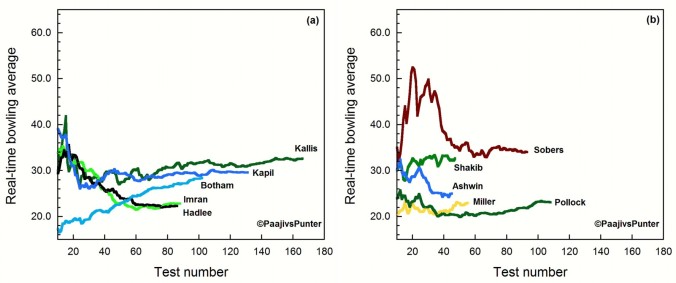

Figure 1: Real-time progression of batting average with each test. To minimize appearance of streaky data, points from the first 10 tests have not been shown.

The traditional favourite metric of batting ability is the batting average (runs scored per dismissal). Historically, a batting average of 50 is opined to be a measure of all-time greatness. Only two players from the all-rounder list have breached this benchmark, following contrasting paths: Sobers reaching it quite early, and Kallis achieving it only by his ~70th test. Imran’s late career showing is captured by his ever increasing trajectory. The others hover between the 27 to 40 marks.

However, is it fair to compare a lower order batsman with a top order one? Wouldn’t a top order batsman have a greater chance of making more runs since he can call upon greater batting support? Valid question.

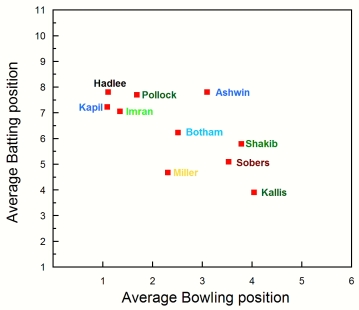

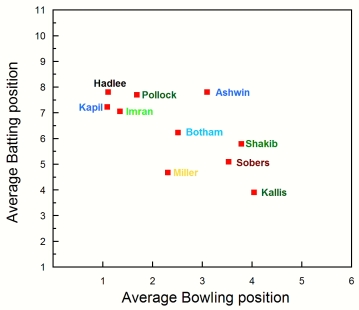

The first deviation between the definition of the all-rounder and career statistics appear in the average batting position (ABP). Sobers, Kallis, Miller and Shakib batted in the top 6; the rest batted mainly at 6 and below. Ashwin’s average batting position belies his recent stint at number 6—his career-to-date ABP is closer to Hadlee’s and Pollock’s.

It must also be noted that the ABP only represents an average. One could mischievously conjure an ABP of 5 with an equal number of innings at numbers 4 and 6 (and none at 5). Hence, in order to take these values in context, the batting position spread has to be investigated as well.

If the percentage spread of innings at every position is examined for each player, more trends emerge: Kallis predominantly batted at 3 & 4, Miller at 4 & 5, and Shakib at 5 & 6; Sobers batted all around the batting order, favouring the number 6 position the most. Perhaps, some of Hadlee’s lower batting average can be attributed to his stints at 8 & 9. In Sobers’ case, the ABP does not correlate with his most frequent batting position.

The real-time progression of ABP also gives great insight about the batting roles played by these all-rounders at different points of time in their careers. Kallis and Miller quickly transformed to middle order batsmen; Imran, Shakib and Hadlee gradually batted one position up the order; Kapil, Pollock and Botham were steady presences in the eleven. Sobers is the one genuine outlier amongst this bunch: he started much lower down the order, worked his way up, and then approached an ABP of 5 towards the end of his career.

From the various batting metrics garnered from the scorecards, it can be confidently said that Sobers, Kallis, Miller and Shakib neatly fit into the definition of top 6 batsmen. The rest batted lower down the order. On the basis of the above data, it can be said that Kapil, Pollock, Ashwin and Hadlee were bowlers who could bat a bit.

However, a complete picture of their all-round credentials can only be obtained after examining bowling statistics as well. The most important statistic for a bowler is the number of wickets. Compared to the runs, wickets are comparably finite (20 in a test match). Hence, auxiliary support needs to be drawn from other information contained in scorecards—such as balls bowled, runs conceded, and bowling position.

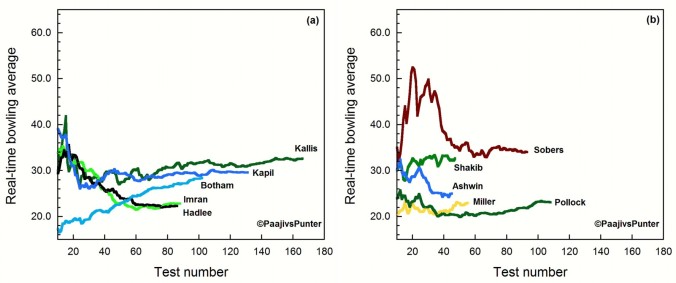

Similar to the batting average, the bowling average is a measure of the bowling ability (runs conceded/wicket taken). It must be noted that this is a good measure as it is the product of the economy rate (runs conceded/balls) and the strike rate (balls/wicket taken). An all-time great bowler typically boasts of a bowling average in the sub-30 mark (with the top pace bowlers hovering around 20).

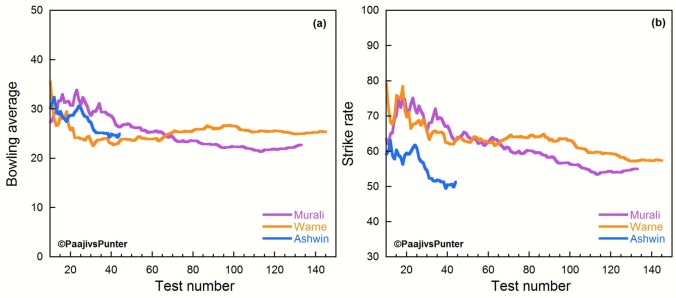

Figure 4: Real-time progression of bowling average with each test. To minimize appearance of streaky data, points from the first 10 tests have not been shown.

The career progress of bowling average charts a totally different journey for many players. Kapil, Kallis, Miller and Pollock have relatively consistent late careers; Botham had a spectacular debut and his performance kept deteriorating with time; Imran and Hadlee went the other way, almost following the same path of improvement. Sobers had an ordinary start, struggled, and then found his footing after his ~40th test. The recent improvement in Ashwin’s statistics is quite visible with a reduction in his bowling average. From a standpoint of bowling average alone, Hadlee, Imran, Ashwin, Pollock and Miller have shown great bowling credentials to date.

Table 3: Average bowling position of each all-rounder

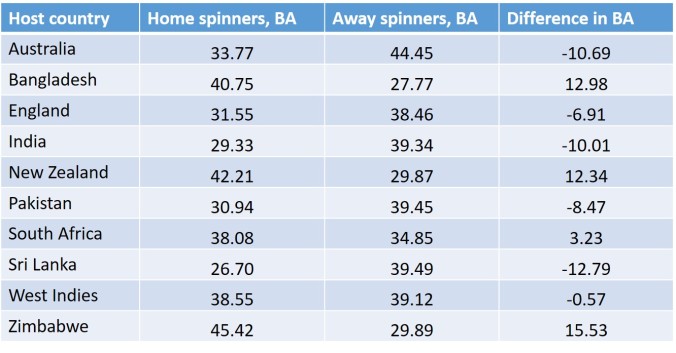

Like the batting counterpart, the Average bowling position (ABoP) of each all-rounder reveals some details about their role within the team. Typically, a team has 4-5 designated bowlers (usually 4). The bowling attack is mostly led by a fast-bowling pair, followed by a first change bowler and a spinner. The first change bowler could be another fast bowler or spinner based on the conditions (3-1 or 2-2 combination). Often, spinners are ploughing a lone furrow from one end while the fast bowlers are rotated from another. Generally, spinners tend to bowl longer spells, and are less effective at taking wickets (on a runs conceded/wicket or balls/wicket basis), but typically grab more wickets per test.

From the ABoP, it can be seen that Imran, Kapil, Pollock and Hadlee were the ones who were given the first use of the cherry; Miller’s and Botham’s numbers resemble first-change bowlers; Ashwin has been the lead spinner and Shakib is the second spinner. Kallis was the 4th seamer—a rough indication of his role in the team. It may seem that Sobers was not as important as some of the others from a bowling perspective, but there is a minor wrinkle in his ABoP value of ~3.5.

The percentage spread of bowling position resolves the issue of Sobers. It must be remembered that Gary Sobers was capable of bowling in a variety of styles (pace and spin), and hence his appearance in the bowling order is quite spread out. He has bowled at the top 2 slots for ~20% of his career.

The above plots confirm the places of Kapil, Hadlee, Imran and Pollock as new ball bowlers; Miller too, has operated with the new-ball ~70% of the time, unlike the ABoP stat, which showed his position to be ~2.3; Botham bowled mainly between 2 and 4. Shakib and Ashwin feature much later due to the fact of them being spinners. Kallis didn’t bowl in ~15% of innings, and bowled behind 3 seamers for more than 60% of his bowling career (with negligible innings at 1 or 2).

The plots of real-time ABoP separate the bowling claims played by the various all-rounders. In the 1980s, everyone except Botham were the top gun bowler for their respective teams. Sobers’ bowling chops are reflected in his continually improving ABoP. At best, Kallis was the fourth seamer for his team. As it has been discussed elsewhere, he was primarily a batsman who bowled really well. Ashwin and Shakib have been important spinners for their sides.

The time-lapse data of wickets per test (WPT) further strengthens the earlier findings: Botham regressed in his wicket-taking ability from his initial high, and Hadlee and Sobers improved to a great degree. Kapil and Pollock had productive, stable careers. In spite of Imran bettering his career average, his wickets per test declined—probably indicating that he bowled much lesser later on in his career. Kallis’ secondary role is confirmed with his WPT value being the lowest amongst the lot. Ashwin, in his short career, has seen many ups and downs.

The real-time balls per test (BPT), too, follow earlier trends. Kallis had a far lesser BPT (~50%) compared to the bowling load of the other players. On this basis, he could be labelled as a batsman who could bowl well rather than an all-rounder in the truest sense. Even though his statistics are quite similar to Sobers, his bowling workload was never in the same league. Every other all-rounder averaged at least ~180 balls per test. In spite of Shakib being a spinner, his BPT is close compared to the other pace bowling all-rounders—this points to Bangladesh not burdening him with heavy bowling responsibilities. Ashwin’s recent BPT values have improved due to his wicket-taking feats.

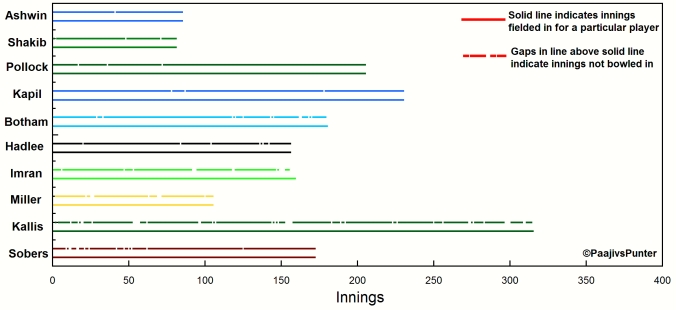

The temporal spread of innings bowled in for each player can be visualized in the above plot. Each solid line indicates the length of bowling career for each player; the line above the solid line contains many gaps, each indicating an interruption in bowling duties. From the above plot, the extent of Sobers’ bowling load is clear; as is the case with almost all the others. Kallis did not bowl for significantly long periods of time, and Imran did not bowl near the end of his career.

How about putting both the skills sets together?

The currency of a test match is runs/wicket. Given than a team has to necessarily capture 20 wickets to win the match, it follows that a winning team will end up with a positive runs/wicket differential w.r.t to the losing team (a declaration would still count as forfeiting the remaining wickets). In a sense, this number plays a similar role to Goal Difference in football.

Therefore, both the batting and bowling contributions are represented by the respective averages—which are essentially runs/wicket. For an all-rounder, the difference between the batting and bowling contributions gives an indication of his net value to the team. This can either be expressed either as a difference or as a ratio.

Test match all-rounders are often measured on the differences between their batting and bowling averages. In a way, they indicate their net contribution to the team. A lot of all-rounders took their time to come to the positive end of the plot. Botham started off as an all-round statistical wonder before finishing with decent numbers overall. Only Kallis and Sobers boasted of a 20+ average difference, but as we’ve seen earlier, the differences in their team roles couldn’t be starker.

Another (uncommon) way of expressing their contribution is to take a ratio of the two averages. A ratio would yield a dimensionless number, and would favour the better bowlers more due to the lesser denominator. A plot of this reveals that only 4 players—Imran, Miller, Sobers and Kallis finished with a ratio of 1.5.

So, who fits the bill as the all-rounder in the most traditional sense?

Table 4: Values of ABP, ABoP and the adjusted sum for the given all-rounders. The Adjusted sum is the sum of the ABP and ABoP. *Note that corrections have been applied in the cases of Ashwin, Shakib (-2) and Sobers (-1) for better representation.

It must be noted that while there are all-rounders in ODIs who have opened both the batting and bowling consistently (Zimbabwe’s Neil Johnson comes to mind), the fast-bowling workload is quite immense in tests, and hence examples of all-rounders who batted up the order are hard to come by. One way of checking their importance to the team would be to sum up their average batting and bowling positions. Since spinners bowl later, a correction of -2 has been applied (-1 for Sobers, considering his bowling variety) to get an adjusted sum.

Figure 12: Representation of ABP versus ABoP for various all-rounders. Note that the correction has not been applied in the spinners’ cases.

Going by the average batting and bowling positions, and the adjusted sum values, Keith Miller fits the definition the most, followed by Sobers. Over years to come, Shakib has a great chance to join this clan due to his middle order batting position (and provided he can be effective as a bowler). What about Ashwin then?

The above plot also shows Ashwin’s value to the team—being the team’s leading bowler (like Kapil, Imran, Hadlee and Pollock). Ashwin might have been the only fifth man to score 300 runs and take 25 wickets in a series, and one of four men to tally the 600 runs-60 wickets calendar year double (with Botham being the other common factor in these two lists); Ashwin might have had a recent fantastic stint at number 6, but he wouldn’t figure any higher up in the batting order even if he were to score 5 more hundreds in 2017. However, he would probably be dropped to make way for another spinner should he continuously perform poorly with the ball for a series or two.

In his relatively short career, Ashwin has shown great all-round credentials and is well placed ahead of many legends around the 45 test mark on many metrics. He has the highest wickets, WPT, five fors, and has the best batting stats when compared to others who batted primarily at number 7 or lower (Kapil, Imran, Hadlee, and Pollock). However, whether he follows the path of Ian Botham or Imran Khan remains to be seen.

Ashwin, being a spinner, has a great chance of a longer career compared to pace-bowling all-rounders. With a longer stint at number 6, he may even get to post higher scores as a batsman. With a little bit of help from the Indian pacers, he should be able to perform better abroad. He has a genuine shot at becoming the premier spin-bowling all-rounder of all time; but, his all-time status and legacy will heavily hinge on what he does with the ball.

Disclaimer: Some of the images used in this article are not property of this blog. They have been used for representational purposes only. The copyright, if any, rests with the respective owners.